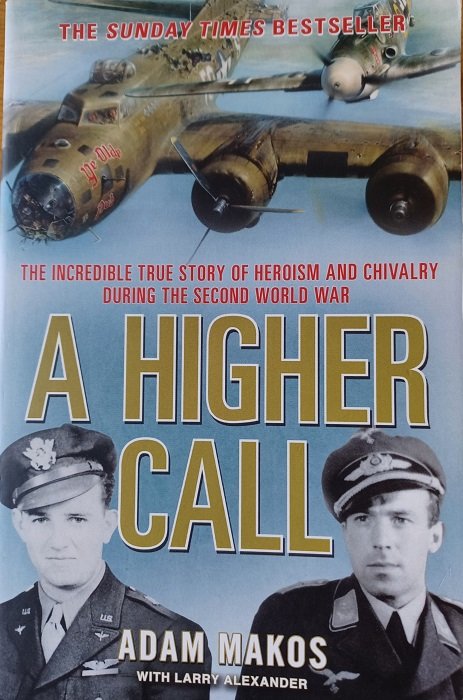

Book Review - 'A Higher Call' by Adam Makos with Larry Alexander

‘Five days before Christmas 1943, a badly damaged Allied bomber struggled to fly over wartime Germany. At its controls was a twenty-one-year-old American pilot. Half his crew lay wounded or dead. Suddenly a Messerschmitt fighter pulled up on the bomber’s tail – the German pilot was an ace, who with a squeeze of the trigger could bring down the struggling bomber.

This is the incredible true story of 2nd Lieutenant Charlie Brown and 2nd Lieutenant Franz Stigler, the two pilots whose whole lives collided that day. It was an encounter that would haunt both pilots for forty years until, as old men, they would seek out one another and reunite.’

Those who have been around my blog are probably aware I’d already written about this incredible encounter in the 2017 post titled, ‘Charlie Brown and Franz Stigler: Compassion Amongst Enemies’.

This book was mentioned in the comments, and, after all this time, I’ve finally gotten around to reading it.

As I was already familiar with the story, I did wonder how much more I’d get from the book and if I’d even enjoy it.

Well, I needn’t have worried; I learned a great deal and I thoroughly enjoyed the book.

When I started reading, I expected there to be equal ‘time’ given to both, Charlie Brown and Franz Stigler, but the book focusses more on Stigler.

Out of 25 chapters, less than half include Charlie and his crew.

In the ‘Introduction’, Adam Makos explains what happened when he contacted Charlie to interview him about the incident.

After agreeing to the interview, Charlie asked Makos if he wanted to know the whole story of what had happened.

When Makos replied that he did, Charlie said he should first learn about Stigler:

‘“In this story,” Charlie said, “I’m just a character – Franz Stigler is the real hero.”’

Franz Stigler was born on the 21st of August 1915 in Bavaria.

His father had been a pilot/observer in the First World War.

He had a brother, August, 4 years his senior, whom he adored.

His mother, a devout Catholic, wished for one of her sons to be a priest; when August decided he wanted to be a teacher, it fell to Franz to fulfil their mother’s wish.

But it didn’t take long for his true love to take precedence – more than anything, Franz wanted to fly.

After graduating from high school, he studied aeronautical engineering, and, soon afterwards, began flight training.

By 1937, he was flying for Lufthansa ‘as an international route check pilot. His role was to establish the quickest and safest flying routes between Berlin and London, and over the Alps to Rome and Barcelona.’

And it was in 1937 that Franz was given his orders to join the German Air Force, the Luftwaffe, as a flight instructor.

In late 1940, he resigned as an instructor to become a fighter pilot.

I learned quite the noteworthy point – very few fighter pilots, if any, were members of the Nazi Party.

Any fighter pilot who was already a Nazi when he joined the German Air Force would have had to have done so when he was quite young.

Those who joined the Air Force were forbidden by the German Defence Law of 1938 to join the Nazi Party because of a German tradition of impartiality that kept the military separate from politics.

However, civilians, as well as the SS and the Gestapo, could join the Party at any time.

In April 1942, Franz, together with other fighter pilots, flew their Messerschmitt Bf-109s to Libya to join the war in Africa.

Messerschmitt Me 109 G-6 fighter of JG-27 (W.Commons)

The officer in charge of Franz was Lieutenant Gustav Rödel, the one who promised Franz, ‘“If I ever see or hear of you shooting at a man in a parachute… I will shoot you down myself.”’

Makos gives us a lot of insight into what life was like for the German fighter pilots in Africa.

He doesn’t only focus on their battles but also details their daily routines in between the flying and fighting, thus humanising them.

Franz Stigler emerges from his 109, Africa (Metapedia)

When we’re introduced to 2nd Lt. Charles Brown, he’s on his final mission of B-17 training school together with his co-pilot, 2nd Lt. Spencer ‘Pinky’ Luke.

Makos gives us interesting little details about each of the crew, turning them into more than just a list of names.

Charlie had had a ‘rough and humble upbringing on a West Virginia farm’.

Pinky, who’d been a mechanic, was ‘from Ward County, in desolate West Texas’.

The navigator, 2nd Lt. Al ‘Doc’ Sadoc, was from New York but looked more like a Texan, and was the only one of the crew who’d been to college.

The bombardier, 2nd Lt. Robert ‘Andy’ Andrews, was from Alabama and ‘followed Doc everywhere’ even though he didn’t drink or swear, unlike Doc.

The top turret gunner, who was also the bomber’s flight engineer, Sergeant Bertrund ‘Frenchy’ Coulombe, enjoyed putting on ‘a Creole-style French accent to amuse the crew’ even though he was from Massachusetts.

Sergeant Hugh ‘Ecky’ Eckenrode, the tail gunner, was from Pennsylvania, a short, quiet soul ‘with a face that looked sad even when he was happy.’

The left waist gunner, Sergeant Lloyd Jennings, the quietest one, ‘spoke in a proper, polite manner’, and was a teetotaller.

Sergeant Dick Pechout, from Connecticut, was the radio operator who loved all things technical.

The ball turret gunner, Sergeant Sam ‘Blackie’ Blackford, was ‘a talkative Kentuckian… as rough and tough as he was personable’ thanks to his backwoods upbringing.

And finally, Sergeant Alex ‘Russian’ Yelesanko, the right waist gunner, ‘tall, burly… from Pennsylvania whose Russian-looking features reflected his ancestry’.

Crew of ‘Ye Olde Pub’ (W.Commons)

(Front kneeling L-R) 2nd Lt. Charles "Charlie" Brown, 2nd Lt. Spencer "Pinky" Luke, 2nd Lt. Al Sadok, and 2nd Lt. Robert Andrews.

(Back standing L-R) Sgt. Bertrand "Frenchy" Coulombe, Sgt. Alex Yelesanko, Sgt. Richard Pechout, Sgt. Lloyd Jennings, Sgt. Hugh "Ecky" Eckenrode, and Sgt. Sam Blackford.

Stationed at Kimbolton in Cambridgeshire, home to the 379th Bombardment Group of the 8th Air Force, Charlie flew ‘his first mission as a new member’, flying as co-pilot with another crew, a way of familiarising a newly arrived pilot to combat ‘before he embarked over Germany with his own crew.’

B-17F formation over Schweinfurt, Germany August 1943 (W.Commons)

One week later, in the early hours of the 20th of December 1943, Charlie would take his crew on ‘his second combat run to Germany’.

The mission, to bomb the Focke-Wulf plant on the outskirts of Bremen, would involve the entire 8th Air Force, with the 379th given the honour of leading them.

In total, the bombers in the air, B-17s and B-24s, heading towards Bremen numbered almost 475, with fighter cover from P-38 Lightnings and P-47 Thunderbolts.

B-24 Liberator, flying over Iwo Jima 1945 (W.Commons)

P-38 Lightning (W.Commons)

P-47D Thunderbolt (W.Commons)

Although the term ‘precision bombing’ was used, it was almost impossible to be precise when only the lead plane was able to aim; the other planes following behind could only drop their bombs blindly… ‘The 8th Air Force measured error in hundreds of yards and even miles. The Germans on the ground measured that same error in city blocks and civilian casualties…. 54 percent of the 8th Air Force’s bombs were landing within five city blocks of their targets. The other 46 percent fell where they were not supposed to. But… the 8th Air Force always aimed at military targets, even if that target was nestled in… a city.’

Charlie’s B-17, ‘Ye Olde Pub’, was one of 21 flying from Kimbolton; with 4 engines per bomber, the combined noise of 84 engines in total must have been thunderous as they prepared for take-off.

The bombers lined up, each taking off a mere 30 seconds apart.

When it was the turn of Charlie’s ‘The Pub’, he ‘pushed all four throttles forward. The bomber vibrated, fighting her brakes.’

At the signal from Pinky, ‘Charlie lifted his feet from the brakes and let the bomber loose. With a roar she tilted her nose slowly downward as she ran… The Pub raced past the fields… When the bomber’s nose broke one hundred miles per hour, Charlie slowly pulled the control column toward his chest, until an invisible gust of air rushed beneath the wings and broke the suction of the earth, lifting the bomber into the sky.’

Charlie, only 21 years old, knew he was now responsible for the lives of his 9 crewmen for the next 7 or so hours.

Almost 4 hours later, they were on their approach to the target, and found themselves in the midst of explosions from flak gunners on the ground.

B-17 bombers flying through dense flak... probably a July 1944 Merseburg mission (W.Commons)

By the time The Pub dropped her bombs, she’d already taken damage.

With 2 faltering engines, The Pub lost speed and began to fall behind as the other bombers gradually disappeared into the distance, heading for home.

The sight of a lone bomber soon drew the attention of German fighters, and Charlie and his men had to, somehow, fight them off.

The flight of the critically damaged bomber, with her crew either dead or injured, some severely, tenaciously limping her way back to England is covered in 3 harrowing chapters.

Even though I knew the outcome, reading the almost excruciatingly detailed events had me on the proverbial edge of my seat.

Adam Makos’ style could be described as simplistic in that his word choice is simple and easy to understand.

He includes a lot of detail, even in the day-to-day stuff, and, it could be argued, some of that could have been trimmed down.

The book reads more like an action novel and not what I would call a typical non-fiction history book.

Like this passage, for example, one of my favourites because of the image it conjures; it’s when Franz and the other pilots fly their planes to Libya:

‘Low and fast, the twelve tan Messerschmitt Bf-109 fighters blasted over the white beaches of Libya. Climbing over the sea cliffs, the fighters soared above the ruins and Hellenic columns of the ancient Greek city of Appolonia.’

To begin with, I wasn’t too sure about this approach, but it didn’t take long for me to be drawn into the story, and I found myself getting emotionally invested, not just with Franz and Charlie, but those around them too.

But what I truly appreciated was the level of detail surrounding the fighter planes and the bombers, and, most especially, the thoughts and emotions of the flyers.

In this, Makos has been ably assisted by Larry Alexander, who not only undertook extensive research, he also helped with the writing.

For someone who has not a clue about the intricacies of such planes and how to fly them, the way Makos described all those details made it clear and easy for me to understand.

I admit I was surprised to learn that, despite their hotshot image, many pilots experienced terror, not exhilaration, on their first combat flight and, depending on the situation, even on subsequent flights.

After suffering the horror of witnessing their comrades die, with planes either crashing to the ground or exploding in front of them, they had to summon the courage to fly again, knowing they might suffer the same fate.

Another thing I appreciated was the inclusion of how the decisions of Hitler and Hermann Goering, the commander-in-chief of the Luftwaffe, impacted the German pilots and their families, and the country.

I had no idea of the intense animosity between Goering and the Luftwaffe; he blamed the pilots for failing to stop the bombers, accusing them of cowardice, looking for the smallest excuse to punish them, especially the officers.

As the war reached its end, Franz and other faithful pilots took their orders directly from officers they trusted and did their best with the faulty, limited resources they had to save the people and cities from the bombers.

Franz Stigler (4th from R) & his pilots at Graz (Metapedia)

Towards the end of the book, we learn how Franz and Charlie eventually found each other, and the significance of Franz’s spontaneous chivalrous action during the war.

Being familiar with a story is one thing; to really know a story is something quite different, and I’m glad I finally read this.

If you’re looking for a story – a true story – about honour, tragedy, and the capacity for human endurance, all wrapped up in thrilling excitement, ‘A Higher Call’ might well be the book for you.