Poetry and Art (6)

‘La Belle Dame Sans Merci’ by John Keats

I didn’t read any Keats till I was well into my 20s; he wasn’t a poet who featured in my schooling years. Shame, really, as I do like his poetry. I rediscovered Keats when I watched the film, 'Bright Star', a couple of years ago, which has since become one of my favourite films.

John Keats was born in Moorgate, London, on 31st October 1795. It was only in the last six years of his tragically short life, from 1814, did he write poetry seriously; he only published in the last four years. Tuberculosis was the spectre that haunted him through his life – his mother died of it when he was 14; and then it claimed his brother, Tom. Keats nursed Tom through his illness until his death in 1818. By that time, Keats himself was already showing signs of the disease.

1818 was also the year he met and fell in love with Fanny Brawne; the following year, he began work on ‘La Belle Dame Sans Merci’, and completed it the same year. It is possible, if one so desires, to read Keats’ love for Fanny, and the knowledge of his impending death into the situation of the doomed knight of the poem … In one of his letters to Fanny, Keats wrote, “I have two luxuries to brood over in my walks … your loveliness, and the hour of my death.” His letters and poems reveal that even as he experienced the pleasures of love, there was also pain, which he resented, most especially the loss of freedom that comes with falling in love.

In 1820, as Keats condition worsened, he was advised by doctors to move to warmer climes, and he left for Italy, with the probable realisation that he would never see Fanny again. After he left, he could not bring himself to read her letters or write to her, though he did write to her mother. He died in Rome on 23rd February 1821, aged 25. It took a month for the news of his death to reach London. When she was told, Fanny remained in mourning for six years, eventually marrying 12 years after Keats’ death.

O What can ail thee, knight-at-arms,

Alone and palely loitering?

The sedge has wither’d from the lake,

And no birds sing.

O What can ail thee, knight-at-arms,

So haggard and so woe-begone?

The squirrel’s granary is full,

And the harvest’s done.

I see a lily on thy brow

With anguish moist and fever dew.

And on thy cheeks a fading rose

Fast withereth too.

I met a lady in the meads,

Full beautiful – a faery’s child,

Her hair was long, her foot was light,

And her eyes were wild.

I made a garland for her head,

And bracelets too, and fragrant zone;

She look’d at me as she did love,

And made sweet moan.

I set her on my pacing steed,

And nothing else saw all day long,

For sidelong would she bend, and sing

A faery’s song.

She found me roots of relish sweet,

And honey wild, and manna dew,

And sure in language strange she said –

“I love thee true.”

She took me to her elfin grot,

And there she wept, and sigh’d full sore,

And there I shut her wild wild eyes

With kisses four.

And there she lulled me asleep,

And there I dream’d – Ah! Woe betide

The latest dream I ever dream’d

On the cold hill’s side.

I saw pale kings and princes too,

Pale warriors, death-pale were they all;

They cried – “La Belle Dame sans Merci

Hath thee in thrall!”

I saw their starved lips in the gloam,

With horrid warning gaped wide,

And I awoke and found me here,

On the cold hill’s side.

And this is why I sojourn here,

Alone and palely loitering,

Though the sedge is wither’d from the lake,

And no birds sing.

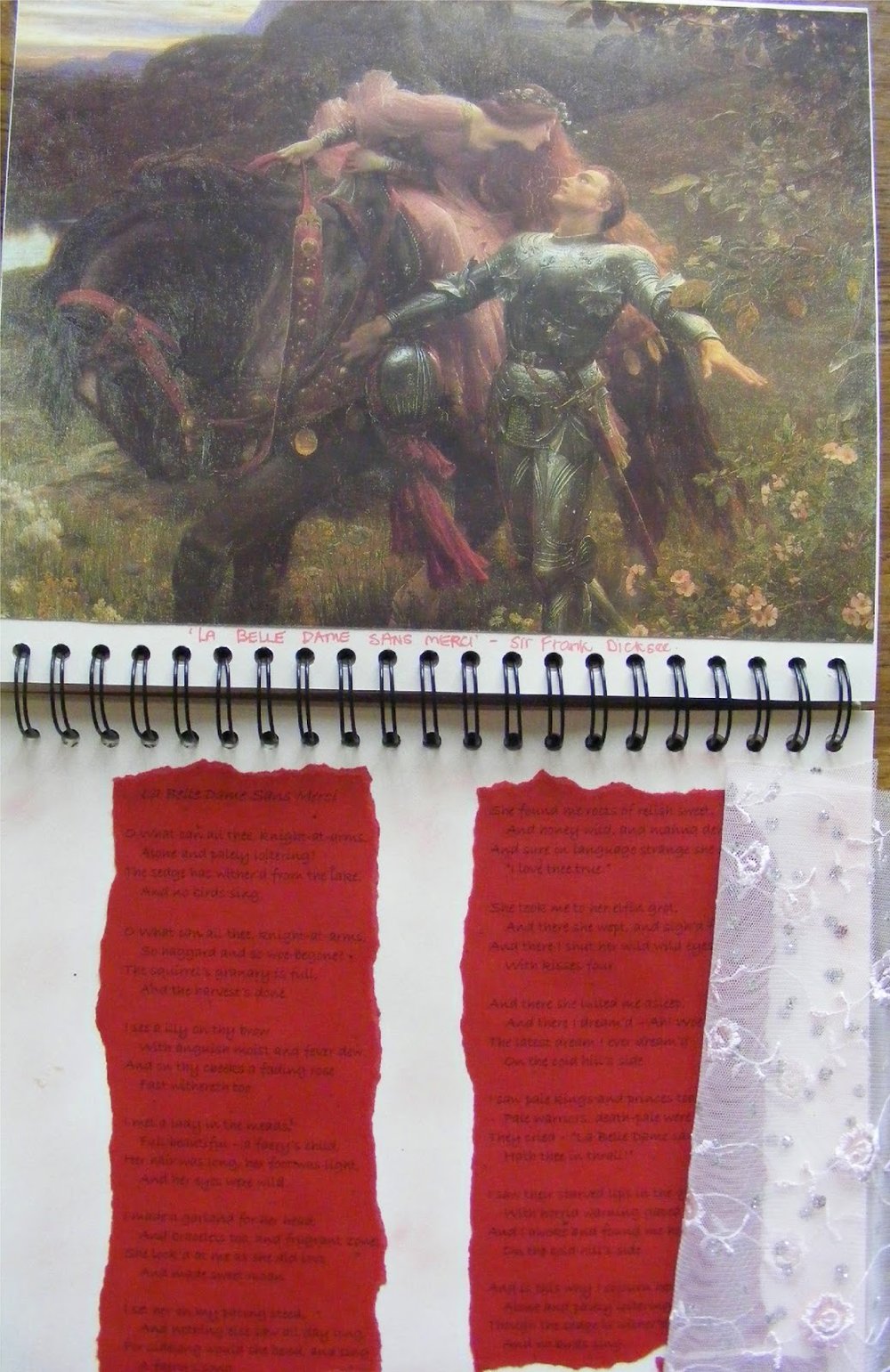

Art - 'La Belle Dame Sans Merci' ~ Sir Frank Dicksee, the original in Bristol Art Gallery and Museum