Favourites on Friday - William Marshal, The Greatest Knight

Also my favourite knight …

William Marshal effigy, Temple Church, London

He was born in 1147 and died in 1219, at the age of 72, remarkable considering the perilous times he lived in. His life was bookended by two major events in British history – the civil war between Stephen and Matilda; and the establishment of the Magna Carta in 1215.

The office of Lord Marshal was originally to do with the keeping of the king’s horses; it later transformed into head of the king’s household troops. Won as a hereditary title by William’s father, John Fitzgilbert, it was passed to the eldest son, and later claimed by William.

William was the fourth son of John Fitzgilbert, the Marshal of the horses in King Stephen’s court. During this time of anarchy, it was not unheard of for men to switch allegiance. Even though he was part of Stephen’s court, John decided to side with Matilda. When, in retaliation, Stephen laid siege to Newbury Castle, John surrendered the 5-year-old William as a hostage. When John refused to comply with Stephen’s demands, Stephen threatened to catapult the boy over the walls. John responded – defiantly? Heartlessly? – “I have the anvils and the hammer to forge still better sons.” Luckily for William, Stephen was taken enough with the young boy’s innocence that he spared him.

William eventually found himself treading the familiar path of the younger son of a lower-ranked nobleman, serving and training in the household of his cousin, William de Tancarville, the Chamberlain of Normandy. By the time he was 20, he was excelling on the local tournament circuit, and gaining in popularity. The primary aim of tournaments was to prepare men for war by teaching them how to fight. Instead of killing their opponents, knights captured them for ransom; in this way, it was possible to build up a tidy fortune, so long as the victorious knight was sensible in what he took and how he spent it.

And then came the career-defining moment of William’s life. In France, amidst a rebellion led by the de Lusignan family, and while escorting Henry II’s queen, Eleanor of Aquitaine, William and his uncle, Earl Patrick of Salisbury were ambushed, and Patrick murdered. Enraged, William fought their attackers, but, badly injured, he was taken prisoner. His actions were enough for Eleanor to escape being captured. Knowing she owed him her freedom, possibly her life, Eleanor ransomed William. He was returned to the court of Henry II, eventually joining the household of the heir apparent, 13-year-old Henry.

Henry II

Henry, the Young King

In 1170, at the age of 15, and in his father’s lifetime, Henry was crowned King of England, and was, thereafter, known as Henry, the Young King. Despite his obsession with tournaments, and dislike of politics, still the Young King felt growing frustration at his lack of power and lands. What should have been a match made in heaven between the young Henry and William was anything but. The Young King and his brothers, Richard and Geoffrey, rebelled against their father, demanding he give them more land and greater power. But Henry II was loath to share. William’s loyalties were put to the ultimate test – though the young Henry was his sworn lord, Henry II was his king.

Traversing the minefield that was the Plantagenet court, it was inevitable that William would make enemies who sought to besmirch his unblemished honour. Rumours were spread that William was having an affair with the wife of the Young King. William was ready to defend his honour in trial by combat, but was banished from court. He spent the following years on the tournament circuit, cementing his popularity and reputation.

In 1183, young Henry and his brother, Geoffrey, once again, rebelled against their father. William returned to court, and, surprisingly, with the king’s permission, was allowed to reunite with his former master. But, after plundering a shrine, young Henry was struck down with dysentery. Henry had taken a crusader’s vow, which he had yet to fulfil. When he realised his end was near, he gave his cloak to William, requesting him to take it to the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. A few days later, the Young King was dead.

William kept his promise, and embarked on a personal crusade to the Holy Land, a crusade that was paid for by King Henry II. Unfortunately, nothing was written about this trip – did William deliberately not make a record of it as it was too personal? All that is known is William Marshal met with the Knights Templar.

On William’s return, he was accepted into the king’s household. Henry II promoted William, and promised him a wealthy heiress for a wife. Already past 40, William believed he would never marry. But, thanks to Henry II, William married Isabelle de Clare, the 17-year-old ward of the king. She was Countess of Pembroke and Striguil, and through this marriage, William became the first Earl of Pembroke, one of the richest and most powerful men in Europe. Even though it started off as a marriage of convenience, evidence points to it becoming a happy one; they had 10 children.

Pembroke Castle - Manfred Heyde

Towards the end of Henry II’s reign, the king had to face yet another rebellion by his sons. While covering Henry’s retreat, William charged Richard, killing his horse, but the heir was unhurt. That was a risky move that could have led to eventual death for William; not only could he have killed the heir, he had openly attacked his future king. After Henry II’s death in 1189, Richard I confronted William about the attack, accusing the man of almost killing him. William replied that he had not been attempting to kill Richard, and that he had struck precisely where he’d meant to – the horse. Fortunately for William, his loyalty was something that had never wavered, no matter who he had served, and Richard favoured this trait in his men. With Richard devoting his time and attention to his crusade, he knew he could trust William to help run the kingdom in his absence, and keep the crown from falling into the hands of his younger brother, John.

Richard I

King John

When John was crowned king in 1199, William found himself having to deal with a ruler who was paranoid, and who did not treat his barons well. John had lost Normandy in 1204, been excommunicated by Pope Innocent III, and proved a most uninspiring leader. Weary of John’s harsh treatment, and being called a traitor, William retreated to Ireland with his family where, under his able management, Leinster thrived.

Meanwhile, John’s problems with the barons intensified; one of the few who came to his aid was William Marshal, despite the manner in which the king had treated him. By 1215, King John was left with little choice but to sign the Magna Carta, which put the king below the law, not above it.

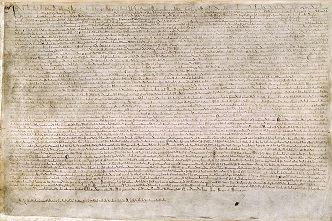

Magna Carta 1215, held at the British Library

The Great Seal of King John, attached to the Magna Carta

But John went back on the charter, and found himself at war with the barons in the First Barons’ War. The barons invited Louis, the Dauphin, to come to England and claim the throne.

William Marshal remained loyal to the king up to John’s death in 1216. He managed to tread a very fine line in that he never rebelled against his king, nor did he associate himself with John’s severe policies. As a result, he was popular with both sides, and was first choice to become regent of the kingdom, and protector to John’s 9-year-old son, Henry, the future Henry III.

The country was still in the midst of war, fighting Louis and the rebel barons. In the Battle of Lincoln 1217, William led the charge against the rebels, and won the battle; he was aged 70. A swift naval victory in the straits of Dover sealed the rebels’ loss, and the civil war ended.

William Marshal died on 24 May 1219, aged 72. What a life he’d led … not bad for a man who started with nothing, was practically illiterate, could not read or write the languages of the courts – French and Latin – and was a landless knight for about 40 years. He also reprinted the Magna Carta in his regency, a fact that is rarely mentioned – I certainly was not aware of this until I started reading what I could find about the man. And yet, despite being in close proximity to kings in tumultuous times, despite being described by the Archbishop of Canterbury, Stephen Langton, as the greatest knight who had ever lived, William Marshal’s story remains a curiously neglected one. Could it be because there are so many gaps in his story?

Whatever the reason, I am thrilled to discover that a new book on William Marshal is due to be released January 2015 – ‘

The Greatest Knight: The Remarkable Life of William Marshal, The Power Behind Five English Thrones’ by Thomas Asbridge, the man who wrote and presented a very good documentary on William Marshal, and also one on ‘The Crusades’ … A new year present for myself, methinks.