Magical Objects Series - Part Five: Ancient Egyptian Mythology

Egyptian Priest Entering Temple by Ludwig Deutsch

To be honest, not sure why I’d planned on doing a post on magical objects of Ancient Egyptian mythology, having already done a series on Ancient Egypt back in 2015. (the section on ‘Ancient Egypt’ is halfway down the page).

This post will complement the one titled ‘Ancient Egypt – Magic and Spells in the Book of the Dead’.

In Ancient Egypt, magic wasn’t something fantastical reserved for only a select few.

Instead, it was seen as part of daily life as it served a practical purpose for all, from royalty to the poor.

Healing prayers and spells against evil were used to ease pain, extend life, and enhance the well-being of the person.

Tools were used to aid the prayers and spells, and included, among others:

Gold and precious stones.

It was believed that gold represented the skin of the gods, silver their bones, and the precious stones their hair.

The Lotus.

Painting from the reign of Akhenaten depicting lotus buds & flowers, from the el Amarna excavation - photo by Keith Schengili-Roberts (WCommons)

As lotus flowers open during the day, and close at night, they were considered a symbol of creation.

Ancient Egyptians believed it gave them strength and power.

The lotus was used in funerary garlands and temple offerings, and perfume was extracted from it.

Amulets.

Both decorative and practical, they were believed to have apotropaic powers to protect the wearer.

Amulets were also placed on mummies to prepare the deceased for the afterlife.

Heart-Scarab amulet - photo by Tim Sneddon (WCommons)

The scarab beetle’s action of rolling its ball of dung along the sands was seen as a representation of the sun’s journey across the sky, and so was thought to represent Ra, the sun god.

It was also seen as a symbol of rebirth and renewal.

Lion Amulet - Metropolitan Museum of Art (WCommons)

A lion amulet was believed to bestow ferocity and bravery on the wearer.

And as lions were said to possess regenerative powers, that, too, would be endowed on the wearer.

Shabtis.

Shabtis in Manchester Museum - photo by akhenatenator (WCommons)

These were figurines ranging in size from about 5 to 30cm, and were usually made of Egyptian faience, though some were made of wood, clay, stone, metal, or glass.

Entombed with royalty and nobles, their purpose was to act as servants for the deceased in the afterlife; a possible translation of their name, shabti, is ‘answerer’.

With such importance attached to spells, I’ll include a few more spells from the ‘Book of the Dead’, the most famous collection of Ancient Egyptian spells, seen as a guide to the afterlife.

As I stated in my post on the ‘Spells in the Book of the Dead’, the Ancient Egyptians considered words powerful; speaking or writing prescribed words for a spell was enough to invoke magic.

The spells, usually written on papyrus rolls and buried with the deceased to protect and sustain him in the afterlife, were the means by which the deceased overcame the obstacles he faced on his way to eternal paradise.

To get to eternal paradise meant entering the regions the living could not go – the sky-realm of Ra, the sun god; and the kingdom of Osiris, the Netherworld, or Duat.

Spell 58 gave the dead the ability to breathe air and have power over water.

Spell 126 tells of the Lake of Fire, a region of the Netherworld, surrounded by baboons and flaming torches. If the deceased was honourable, they had nothing to fear for the waters of the lake turned into food to nourish them, but when approached by the wicked the lake became a mass of deadly flames.

Spell 126 - the Lake of Fire, from the Papyrus of Ani.

Spell 161 was for making an opening in the sky for the breath of life to enter the deceased:

‘As for any noble dead for whom this ritual is performed over his coffin, there shall be opened for him four openings in the sky… As for each one of these winds which is in its opening, its task is to enter into his nose.’

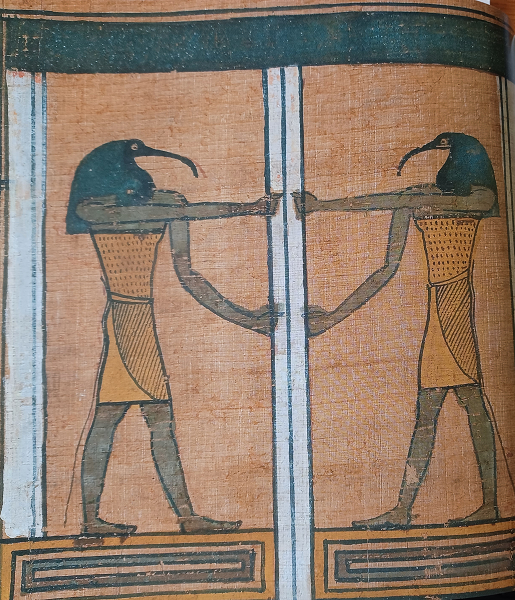

Spell 161 - Two of four figures of the god Thoth, who is said to make an opening in the sky to release the north, south, east and west winds – from the Papyrus of Hor.

Spell 182, considered rare, was one of the spells for when the deceased had a more passive role, and spells and images were used to call forth protective forces to shield him from harm.

The rows of minor deities were illustrated armed with knives, snakes, and lizards, indicating their control over hostile powers.

Spell 182 - minor deities painted on the coffin of Horaawesheb.

(Images for the spells are from my copy of The British Museum book, ‘Spells for Eternity’ by John H. Taylor.)