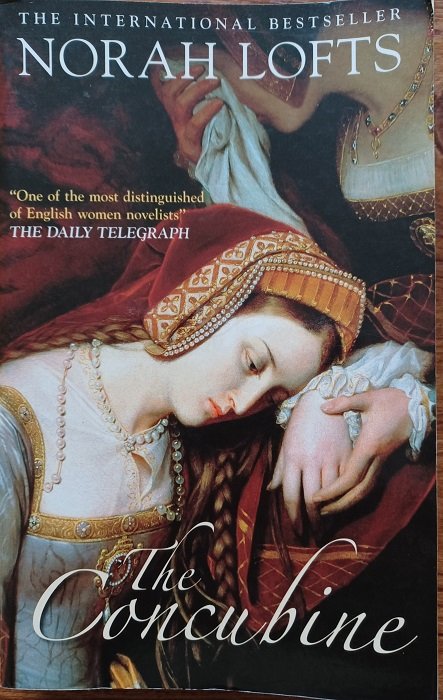

Book Review - 'The Concubine' by Norah Lofts

‘The Concubine’ by Norah Lofts

‘“All eyes and hair” a courtier had said disparagingly of her – and certainly the younger daughter of Tom Boleyn lacked the bounteous charms of most ladies of Court. Black-haired, black-eyed, she had a wild-sprite quality that was to prove more effective, more dangerous than conventional feminine appeal.

The King first noticed her when she was sixteen – and with imperial greed he smashed her youthful love-affair with Harry Percy and began the process of royal seduction…

But this was no ordinary woman, no maid-in-waiting to be possessed and discarded by a king. Against his will, his own common sense, Henry found himself bewitched – enthralled by the young girl who was to be known as – The Concubine…’

For someone who enjoys historical fiction, I’m embarrassed to confess I have never read anything by Norah Lofts.

That’s the reason I picked her book from the October 1963 bestseller list I blogged about last week.

I’ve read a few books about Anne Boleyn and Henry VIII, mainly historical and at least one fictional account, so I know their story but was still curious as to how Lofts would present them.

There is no singular point of view in this book – we start with Anne’s lady’s maid, Anne herself, Henry, Cardinal Wolsey, Queen Catherine, and others.

Also, there are multiple viewpoints in a single chapter, which can be a tad confusing if the reader isn’t paying attention as there’s nothing to signal the change in viewpoint.

Each chapter begins with a passage from a selection of historical books/references, the setting and date, all of which set the stage for what occurs in that chapter.

And so, the first chapter begins with a passage from ‘The Life of Cardinal Wolsey’ by his gentleman-usher, George Cavendish:

‘It was devised that the Lord Percy should marry one of the Earl of Shrewsbury’s daughters – as he did afterwards. Mistress Anne Boleyn was greatly offended with this, saying that if ever it lay in her power she would work the Cardinal as much displeasure as he had done her.’

The setting is Blickling Hall in Norfolk, one of the houses of Anne’s father, Thomas Boleyn, and the date is October 1523.

The story begins from the point of view of a fictional character, Emma Arnett, who has been charged with looking after her new mistress, Anne Boleyn, sent away from Court back to her father’s house.

Anne had spent her younger years in France in the service of Queen Claude and had recently returned to England where she’d been given a place among Queen Catherine’s women.

The sixteen-year-old Anne ‘had no looks to speak of, no bosom even… Her hair and her eyes were noticeable, but they were black, and at Court brunettes were out of fashion. And out of fashion, too, was anything French… Anne… had a marked French accent…’

Also weighed against her was the fact her elder sister, Mary, had been the King’s mistress.

Yet, ‘she had caught the eye of young Harry Percy, heir to the Earl of Northumberland… [he] could… have married almost anyone; and he proposed to marry Anne Boleyn.’

Inexplicably, to the surprise of all, the powerful Cardinal Thomas Wolsey intervenes, telling Harry, who is attached to his household, ‘that his notion of marrying Anne Boleyn must be abandoned.’

So, Anne leaves Court and returns to her family home at Hever Castle, breaking the journey at Blickling Hall.

But she will forever hold the Cardinal responsible for robbing her of love and happiness.

The next chapter, still in October 1523, takes the reader to York House, the residence of the Cardinal, with the historical passage taken from ‘Letters and Papers of the reign of Henry VIII’:

‘Whereas the King for some years past had noticed in reading the Bible the severe penalty inflicted by God on those who married the relicts of their brothers, he began to be troubled by his conscience.’

After discussing state affairs, Henry tells the Cardinal he wants to discuss ‘“a matter of my conscience.”’ – he’s convinced he’s been living in sin with Catherine, his brother’s wife, for fourteen years.

The Cardinal is genuinely perplexed and assures Henry that he has nothing to worry about for ‘“the Pope himself declared your brother’s marriage null and void. It was never consummated…”’

But Henry argues that, although he has a daughter, Mary, he has no sons; ‘“For a King to have no son is to be childless…”’ and he knows he is capable of fathering sons, for he has an illegitimate son.

Henry believes the ruling of the Pope who’d annulled the marriage of Henry’s brother, Arthur, to Catherine, and giving Henry leave to marry her, had been made in error.

He wants the current Pope to look into it, ‘“… find some flaw in [the] ruling and retract the annulment. That would make me free to re-marry and try again.”’

The Cardinal puts forward various arguments, not least the potential of making the Princess Mary a bastard, and the popularity of the Queen herself among the common people.

Inwardly, Henry recoils from the thought of telling Catherine, deciding it will be better to tell her after the Pope makes his decision.

Leaving the matter with the Cardinal, Henry says, ‘“… since the weather has cleared, I’ll have a few days’ hunting down at Hever.”’

It takes a few moments after Henry has left for the Cardinal to realise that Hever is where Anne Boleyn is; it was the King who had told him to break off the affair between Harry Percy and Anne as he’d wanted Anne to marry another which would settle a dispute Henry had.

But did the King have other plans that he hadn’t discussed with the Cardinal, his chief minister?

Lofts takes us through the familiar story; Henry’s determination to have Anne, as he had had her sister; Anne doing the one thing no one else has done – saying ‘no’ to the King for she is equally determined to be more than a mistress to be discarded; Catherine’s unyielding refusal to have her marriage to Henry annulled, and having their daughter, Mary, declared a bastard.

For the most part, I enjoyed the book and Lofts’ descriptions as when Henry finally tells an unsuspecting Catherine of his firm belief that their marriage is unlawful; instead of dialogue, Lofts describes Catherine’s emotions:

‘… it was as though at one minute she had been standing on a safe sunlit terrace overlooking a flat sea, rippling hyacinth and sapphire and jade, and the next minute a great cold, slate-grey wave had come up and engulfed her, swept her down, battered her against sharp rocks and then thrown her back, dying, but not dead, limp, broken and breathless on some strange and desolate shore.’

And her description of the people gathered at the Cardinal’s Court to investigate the validity of Henry’s marriage to Catherine:

‘… the hushed sound of a number of people gathered together and waiting, the shoe scraping the floor; the small quickly smothered cough, the rustle of silk.’

I’ve always been more on Catherine’s side, but this novel made my sympathise with Anne as Lofts has written her as a more human character, instead of the usual portrayal of a one-note crafty, power-hungry woman, hell-bent on becoming queen.

Anne chose the more dignified, albeit more difficult, path of not giving in to Henry’s amorous attention, but made him wait until she could be his queen, which, to his credit, he did.

Unfortunately, neither of them could have known it would, in Lofts’ version, take nine long years; Catherine, a staunch Catholic, fought for the validity of her marriage to the bitter end.

And that long wait would eventually colour the relationship of the King and his second wife.

A couple of reasons why I didn’t totally enjoy this book, the first being the multiple points-of-view.

The story involves quite a few characters, including those who played major roles in the history of the time, yet so few are fleshed out, and its easy to mistake one for another.

The other reason is, while I realise this is historical fiction and I expect there to be a few changes, there are at least two instances where the change is so drastic as to leave me perplexed.

The passage at the beginning of chapter three is from ‘Lives of the Queens of England’ by Agnes Strickland; ‘There is reason to believe that Anne was tenderly attached to her stepmother, and much beloved by her…’

Except Anne didn’t have a stepmother; her own mother, Elizabeth Howard, was still alive, and died two years after Anne’s execution.

I don’t think Lofts introduced the stepmother simply because she wanted to.

This article, ‘Anne Boleyn’s Stepmother: A Life Not Lived’, explains the confusion that left many early writers and scholars believing Elizabeth Howard had, indeed, died while Anne was still young and that her father, Thomas, had remarried.

The other instance happens at the end, which I won’t mention as that’s spoiler territory, but those events are well documented, so I don’t know why Lofts decided to change it as it took me out of the story and coloured my overall enjoyment.

I’ve read books written earlier than ‘The Concubine’, which was written in the 1960s, and have not had a problem with the styles of the time, but the jumping around of viewpoints did start to grate after a while.

So, I can’t say for certain when and if I will read any of Norah Lofts’ other works.

Having said that, if you’re looking for a piece of historical fiction to do with Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn, this is a good read as Lofts does a decent job of portraying what Anne’s life might have been like, and Catherine’s also following Henry’s decision to declare their marriage unlawful.