Art on Friday - Lawrence Alma-Tadema

I have loved the art of Alma-Tadema since I don’t know when. The first time I saw his art was on a calendar. Over the years, I’ve collected calendars, postcards and art prints of his paintings.

Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1870)

Lawrence Alma-Tadema’s birth name was Laurens Alma Tadema. He was born on 8th January 1836 in Dronriip, a village in the province of Friesland in the Netherlands. His father, Pieter, a notary, already had three sons from a previous marriage. Laurens was his third and youngest child with Hinke Dirks Brouwer. Their second child was a daughter, Artje; sadly, their first child had died young.

In 1838, the family moved to Leeuwarden. When Laurens was four, Pieter died. Hinke was left with five children; she also looked after her three step-sons. As she had a great love of art, she made sure the children’s education included drawing lessons.

The original plan was for Laurens to become a lawyer. However, in 1851, when he was fifteen, he suffered a physical and mental breakdown. Doctors diagnosed him as consumptive, meaning he was suffering from tuberculosis and gave him only a short time to live. Instead of carrying on with legal lessons, he was allowed to spend what time he had left doing what gave him pleasure, which was drawing and painting. He gradually regained his health and decided to pursue a career as an artist.

The following year, 1852, he entered the Royal Academy of Antwerp in Belgium. During his four years there, he won several awards.

The historical accuracy that Laurens would become known for was thanks to Louis Jan de Taeye; not only was he a painter, he was also a history professor at the school.

Laurens eventually settled in Antwerp and began working with the highly respected Belgian painter and printmaker, Baron Jan August Hendrik Leys. It was under his guidance that Laurens painted his first major work, ‘The Education of the Children of Clovis’, in 1861.

'The Education of the Children of Clovis' (1861)

The painting took the art world by storm when it was exhibited that same year at the Artistic Congress in Antwerp.

In the mid-1860s, Laurens decided to focus more on the themes of life in Ancient Egypt. In 1862, he left Leys’ studio to start his own career.

Laurens’ mother died in January 1863. In September that same year, he married Marie-Pauline Gressin Dumoulin, the daughter of a French journalist. They had three children. Unfortunately, the oldest, their only son, died of smallpox when only a few months old. Their first daughter, Laurence, was born in 1864 and would become a novelist while Anna, born in 1867, would emulate her father and become a painter. Neither girl would marry.

Anna (front) and Laurence (1873)

The couple spent their honeymoon in Italy and Rome. This was Laurens’ first visit to Italy, the beginnings of his interest in depicting the life of ancient Greece and Rome, which would inspire him in the coming years.

In 1864, Laurens met Ernest Gambart, the highly influential print publisher and art dealer. At the time, Laurens was painting ‘Egyptian Chess Players’. Highly impressed, Gambart ordered 24 pictures and arranged for 3 of Laurens’ paintings to be shown in London.

'Egyptian Chess Players' (1865)

In 1865, after relocating to Brussels, Laurens was named a knight of the Order of Leopold.

Following years of ill health, in May 1869, Pauline died of smallpox; she was 32. Heartbroken, Laurens didn’t paint for four months. Luckily, his sister, Artje, was living with the family, and she looked after her young nieces. She stayed on with her brother until she married in 1873.

Laurens himself started to suffer from a medical problem which the doctors seemed unable to diagnose. Gambart advised him to go to England for medical help, and he did so in December 1869. While at the home of the painter, Ford Madox Brown, Laurens met Laura Theresa Epps. It was love at first sight for him.

In September 1870, along with his daughters and Artje, Laurens relocated to London, his decision influenced by his feelings for Laura Epps and the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War.

It didn’t take Laurens long to propose to Laura, but her father was opposed as she only eighteen while Laurens was thirty-four; he insisted they get to know one another better first.

They married in July 1871. Laurens’ second marriage was a happy one, which lasted many years. Although they didn’t have any children of their own, Laura was happy to be stepmother to Laurence and Anna.

As Laura Theresa Alma-Tadema, she was a highly regarded artist in her right.

'At the Doorway' ~ Laura Theresa Alma-Tadema

She also appeared in many of her husband’s paintings, the most notable being ‘The Women of Amphissa’ (1887).

'The Women of Amphissa' (1887)

Laurens would eventually adopt the more English spelling of ‘Lawrence’ and incorporate ‘Alma’ into his surname to ensure that he would appear at the beginning of exhibition catalogues.

Alma-Tadema continued to ride high on his success. In 1873, he was made a British Denizen by Queen Victoria by letters patent; he was the last to be granted the honour. Denizens were allowed certain rights usually only enjoyed by the monarch’s subjects, including the right to hold land.

Six years later, in 1879, Alma-Tadema was granted what was, for him, his most important award – he was made a full Academician. Three years later, a major exhibition was organised at the Grosvenor Gallery in London, showing 185 of his paintings.

One of his most famous paintings, ‘The Roses of Heliogabalus’ (1888), depicts the decadent Roman Emperor, Elagabalus (or Heliogabalus), suffocating his guests at an orgy with a cascade of rose petals. To ensure the authenticity of the rose petals, blossoms were sent weekly from the Riviera to Alma-Tadema’s studio for four months during the winter of 1887-1888.

'The Roses of Heliogabalus' (1888)

Alma-Tadema was a fun loving, mischievous man who revelled in wine and parties. He was prone to sudden outbursts of temper, which never lasted long. His perfectionism, which encompassed every aspect of his life, and his excellent business sense made him one of the wealthiest artists of the 19th century.

In time, his output decreased, because of failing health and his preoccupation with decorating his new home.

In 1899, he was Knighted in England, only the eighth artist from the Continent to be so honoured.

Despite his age, Alma-Tadema continued to expand his artistic interests, designing furniture and theatrical costumes while still finding time to produce ambitious paintings like ‘The Finding of Moses’ (1904).

'The Finding of Moses' (1904)

In August 1909, aged only 57, Alma-Tadema’s beloved wife, Laura, died, leaving him grief-stricken.

His last major composition was ‘Preparation in the Coliseum’ (1912). In the summer of that year, accompanied by his daughter, Anna, he went to Kaiserhof Spa in Germany for medical treatment.

'Preparation in the Coliseum' (1912)

Lawrence Alma-Tadema died in Germany on 28th June 1912, aged 76. He was brought back to London and buried in a crypt in St Paul’s Cathedral.

Alma-Tadema’s final years saw the rise of modern art, which he didn’t approve of. The changing attitudes of the public and artists led to his paintings being heavily criticised. The art critic, John Ruskin, declared Alma-Tadema “the worst painter of the 19th century”. Following this period, Alma-Tadema faded into obscurity.

One of his most celebrated works, “The Finding of Moses”, illustrates the changing fortunes of the painter’s reputation. In 1935, it was sold for £861; in 1942, for £265; in 1960, it was “bought in” at £252 as it failed to meet its reserve.

In May 1995, that same painting was auctioned at Christies in New York and was sold for £1.75million. In 2010, it was sold at Sotheby’s New York for over $35million, a record for a Victorian painting. And in 2011, Sotheby’s sold ‘The Meeting of Antony and Cleopatra’ for $29.2million.

'The Meeting of Antony and Cleopatra' (1883)

Alma-Tadema’s archaeological research was so thorough that the buildings featured in his paintings could have been built using Roman tools and methods. That, coupled with his perfectionism, led to his paintings being used as inspiration by Hollywood directors for films set in the ancient world, like ‘Ben Hur’ and ‘Cleopatra’. For his remake of ‘The Ten Commandments’, Cecil B DeMille was said to have spread out prints of Alma-Tadema’s paintings so his set designers could see the look he was after.

But it wasn’t only the epic films of yesteryear that used Alma-Tadema’s paintings as source material. They were the central source of inspiration for ‘Gladiator’, and for the interior of Cair Paravel castle in ‘The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe’.

As always, the hardest part for me was choosing which images to include…

'An Audience at Agrippa's' (1876)

'Pandora' (1881)

'Sappho and Alcaeus' (1881)

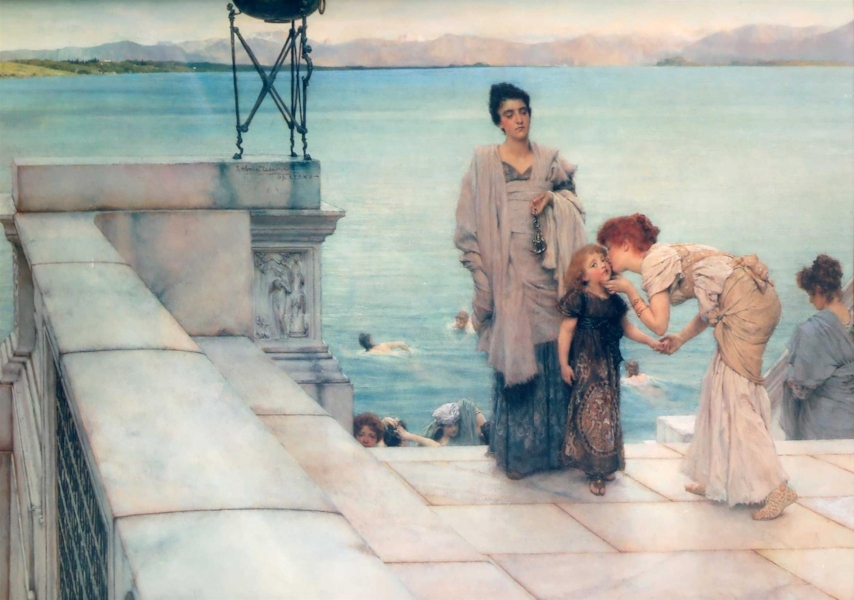

'The Parting Kiss' (1882)

'The Way to the Temple' (1882)

'Welcome Footsteps' (1883)

'The Roman Potter' (1884)

'A Reading from Homer' (1885)

'The Triumph of Titus' (1885)

'A Dedication to Bacchus' (1889)

'An Earthly Paradise' (1891)

'A Kiss' (1891)

'Comparisons' (1892)

'Unconscious Rivals' (1893)

'Spring' (1894)

'A Coign of Vantage' (1895)

'The Colosseum' (1896)

'Among the Ruins' (1902-1904)

'Silver Favourites' (1903)