The Sunday Section: Travel - British Museum and Ancient Egypt's Sunken Cities

Seems like forever since we’ve been to an exhibition at the British Museum. This particular one I’ve been wanting to visit since it opened earlier this year. It finishes at the end of the month; when last Saturday presented us with the opportunity to go, off we went. Bonus – we got to enjoy it with my cousin from America and his lovely wife; they were here on holiday and it was our chance to catch up as we also had lunch together afterwards.

As always with special exhibitions, photography is not allowed. So, I did my usual and bought the book of the exhibition, and I’m so glad I did. The wealth of information, not to mention the stunning pictures, made it well worth the price. Again, as I always do, I’ve taken a few pictures from the book with the sole intention of giving those who didn’t get a chance to visit the exhibition a taster of how spectacular the finds are.

For more pictures and videos, I urge you to visit the site of the French underwater archaeologist, Franck Goddio, who led the expedition conducted by the European Institute for Underwater Archaeology; they’ve been working on it for 20 years.

“Thonis… in early times was the trading port of Egypt…” ~ Diodorus Siculus (Greek historian)

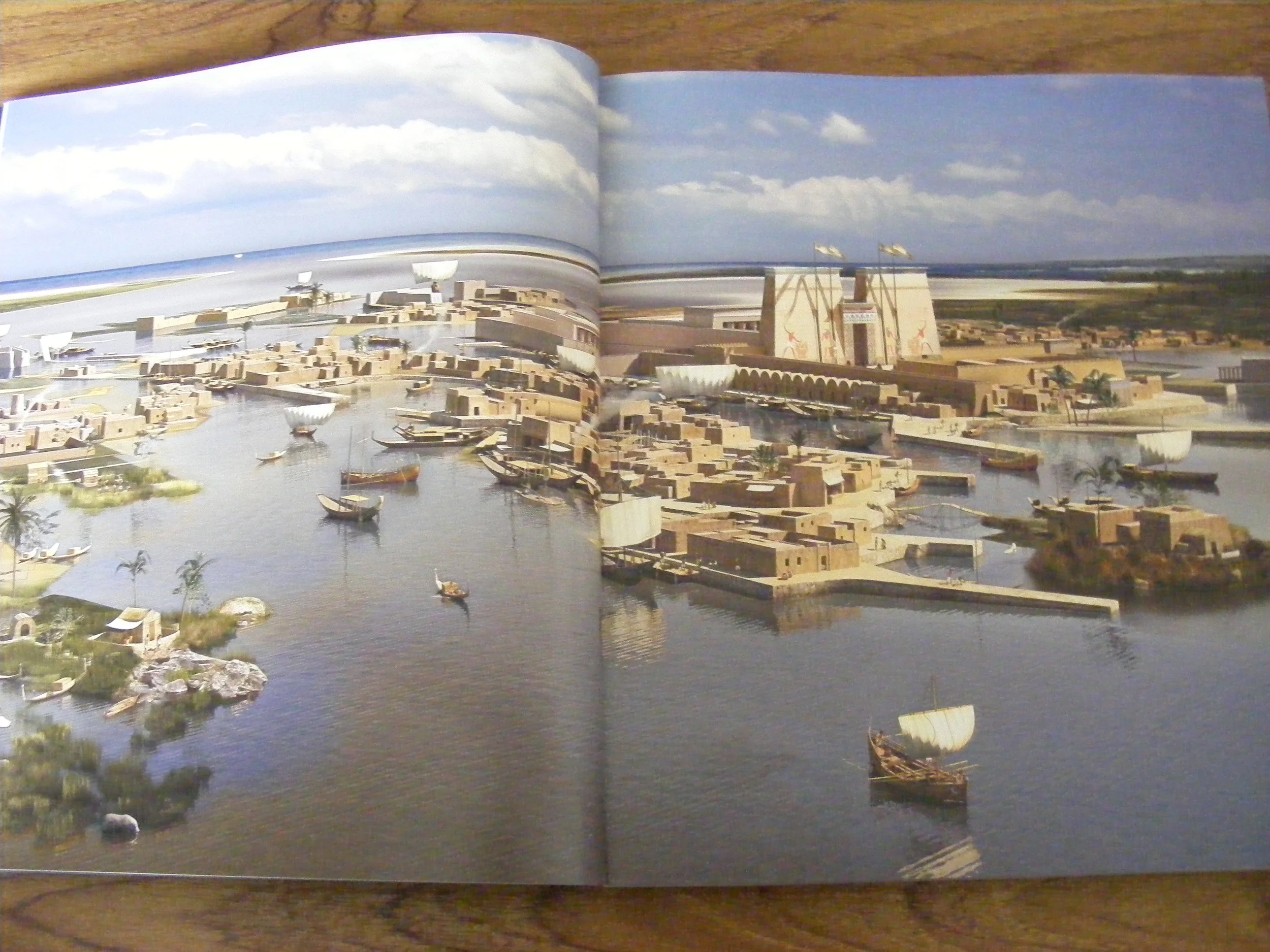

Located at the mouth of the Canopic, the westernmost branch of the Nile, the cities of Thonis-Heracleion and Canopus flourished thanks to the flow of different people and ideas, and the exchange of goods. Unfortunately, this prime site was also unstable; the landscape was made up of lakes and marshes. Eventually, having been abandoned by their inhabitants, possibly because of earthquakes and tidal waves, the cities sank beneath the sea. Research shows that the submerging of the area was caused by a variety of factors including the slow subsidence of the land, and ‘liquefaction’, a process where solid ground literally turns into a liquid.

But before this happened, the area was well-known. It was here that Greeks came into contact with the Egyptian civilisation. According to Greek myth, it was here that Herakles first set foot in Egypt, and this gave the Canopic it’s alternative name, the Heracleotic. According to Greek stories, the city of Canopus owed its name to Canobos, who was pilot to King Menelaus, the husband of Helen of Troy.

It was during the 26th dynasty, the Saite dynasty (664-525BC), that the close relations between Egypt and Greece began. Psamtik I, the founder of the Saite dynasty, drafted Greek mercenaries into his army; both countries traded extensively; Greek aristocrats visited Egypt; and Greek traders were allowed to settle in Thonis-Heracleion and Naukratis, which was an inland harbour.

Naukratis was unique in that it was, both, a royal Egyptian port and a Greek port of trade. The sanctuaries found here were dedicated to patron deities of seafaring – the Dioskouroi, who were the twin sons of Zeus; and Aphrodite, who was also the guardian of safe voyages. There were also sanctuaries dedicated to Hera, Apollo and Zeus. The earliest stone temple for Apollo was built around 560BC at Naukratis.

It was those who participated in the daily life and rituals of the people of Egypt – like Greek traders and mercenaries – who would have been at the forefront of enabling understanding between Egypt and Greece. They would have been the ones taking, not only goods, but also Egyptian ideas about the afterlife and the origins of the gods, knowledge of medicine and craftsmanship, back to their homeland.

The Decree of Sais - a royal decree issued by the pharaoh Nectanebo I, regarding the taxation of trade passing through Thonis-Heracleion and Naukratis. About 6.5ft tall, the clarity of detail is astounding, considering it is almost 2400 years old.

In 332BC, Alexander the Great conquered Egypt, freeing it from the unwelcome rule of Darius III, Great King of Persia. Although he was a foreign conqueror, the Egyptians hailed Alexander as their liberator for they greatly disliked the Persians. Taking up residence in Memphis, Alexander performed the traditional duties of a pharaoh, including making sacrifices to the local royal god, the Apis bull. While maintaining his Greek heritage, Alexander was successfully accepted in Egypt. He crossed the Libyan Desert to the oracle shrine of Zeus-Ammon, an Egyptian god with Greek and Libyan components. The oracle there recognised him as the son of Zeus-Ammon, and Alexander’s rule was seen as divinely ordained.

Following Alexander’s death in 323BC, it was his trusted friend, Ptolemy, who took over Egypt. He was crowned in 305BC, and as Ptolemy I Soter I, he founded a new dynasty, the Ptolemies, who ruled until the reign of Cleopatra III. Under the Ptolemies, the city of Alexandria grew into one of the greatest intellectual and cultural centres of the ancient world, which benefitted the nearby cities of Thonis-Heracleion and Canopus. The Ptolemies were also responsible for building some of the best-known temples, including Dendera, Edfu and Philae.

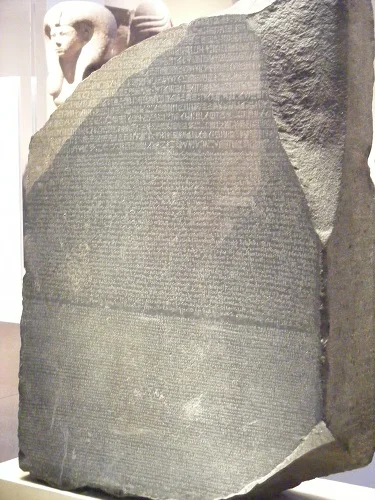

The Rosetta Stone bears a decree, which established the divine cult of Ptolemy V Epiphanes, ‘a token of gratitude from Egyptian priests for restoring cosmic order (maat) by fulfilling his cultic duties’. The decree is written in 3 scripts – hieroglyphic, demotic and Greek.

Rosetta Stone, British Museum

This royal cult did not replace that of the deities but, instead, enhanced it. Neither was it limited to the male ruler for it also embraced the cult of the queen; the mother, wife or daughter of the pharaoh were usually portrayed with divine attributes. The daughter of Ptolemy I Soter I, Arsinoe, gained divine status after her death, and was very popular with both, Egyptians and Greeks, who worshipped her as a Greco-Egyptian goddess. The Egyptians identified her as Isis, while the Greeks saw her as Hera and Aphrodite.

Statue of Arsinoe II

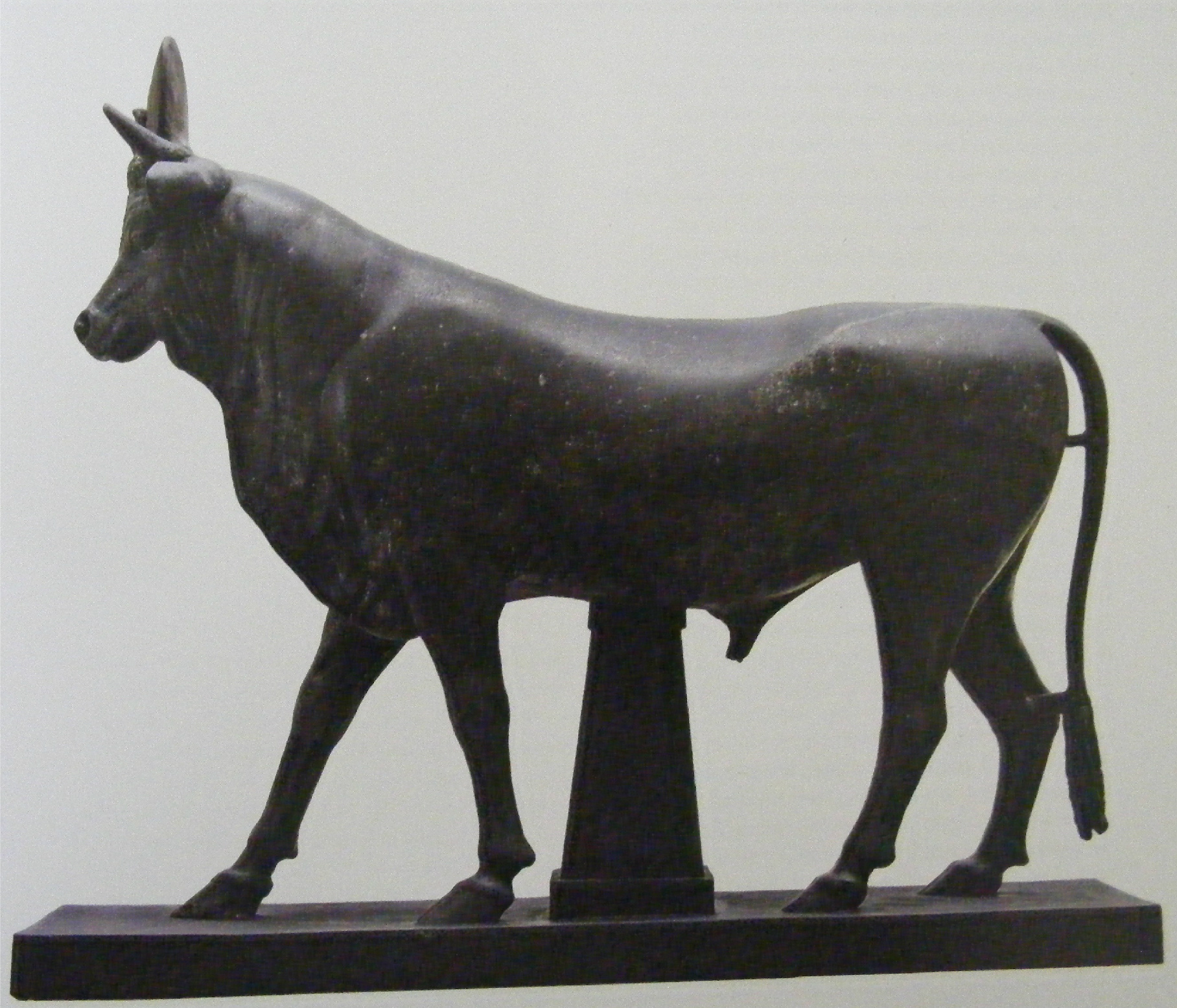

The patron deity of Alexandria and the protector of the Ptolemaic dynasty is one I’d never heard of until I saw him at the exhibition – Serapis. His name is derived from Osiris-Apis, the sacred bull of Memphis and a form of Osiris unique to the area. The Apis bull was carefully selected; he had to have certain markings, and was seen as a representative of the creator god, Ptah, who was also the chief deity of Memphis. The bull was crowned like a pharaoh, served by priests and had his own harem of cows. On his death, the bull became Osiris-Apis. Serapis is seen to be a Greek version of Osiris-Apis, and an amalgamation of Zeus, Hades, Dionysus and Asklepios (god of medicine).

Serapis bust from Alexandria

The Apis bull, Alexandria. This statue is life-size, just over 6ft in height and 6.7ft in length. Again, the detail is amazing.

I thought, at this point, we were nearing the end of the exhibition. How wrong I was. We were at the ‘Myth and Mysteries of Osiris’. After the part detailing the ‘myth’, which involved the death and resurrection of Osiris, there was ‘the Mysteries of Osiris’, the most important ritual celebrations of the year. It took place in the month of Khoiak, the last month of the Nile Inundation when the flood waters receded, and the fields were ready for cultivation. The Inundation season itself was called Akhet, and lasted from mid-July to mid-November.

Osiris seated, Saqqara. We couldn't get over how 'new' some of the statues looked; how did the craftsmen achieve the satin polish?

False door, Sais. False doors were imitation doorways placed in tombs. They faced west, linking the living and the dead. Here, Osiris is the central figure flanked by the goddesses Isis and Nephthys.

Priests made a figure of Osiris called an Osiris ‘vegetans’, which was basically a corn mummy. Earth, barley and floodwater were placed in 2 halves of a golden mould, and watered until the plants sprouted; this symbolised eternally renewed life. The Osiris vegetans was then included in a ritual event, carried on a papyrus barque on the sacred lake of the temple. In total, 34 boats were sailed, each carrying a deity; the lamps on the boats numbered 365, representing the days in the year.

This ornament, called a pectoral, was worn on the chest; it was found in the grave of king Sheshonq II at Tanis. It depicts the solar barque sailing on the primeval waters under a star-filled sky, flanked by the goddesses Isis and Nephthys.

The Greek god who was likened to Osiris was Dionysus. Herodotus wrote that he learnt of this from Egyptian priests; later, Diodorus Siculus and Plutarch noted similarities between the 2 deities. Dionysus brought civilisation to humanity; he was dismembered by the Titans and revived by Rhea who reassembled his limbs; and he was “the lord and master… of the nature of every sort of moisture” (Plutarch).

Dionysus was not the only Greek god who found his counterpart in an Egyptian deity. Apollo was likened to Horus; the Titan Typhon to Seth; and Hermes’ counterpart was Thoth. As for the rest of the pantheon – Amun was linked to Zeus; Mut to Hera; Khonsu to Herakles; Isis/Hathor to Demeter/Aphrodite; and Neith to Athena.

The exhibition finished with ‘Egypt and Rome’, the time of Cleopatra and Marc Antony. By this time, we’d been there for over 2 hours, and exhibition-fatigue had set in; I admit I didn’t pay much attention to the last part.

Ibis mummy, Saqarra. Associated with Thoth, the god of wisdom, ibis was one of the most important animals worshipped by the ancient Egyptians. The dark patch on the linen wrappings is resin. The X-ray on the right shows that it contains a completely preserved ibis.

Queen (possibly Cleopatra III) dressed as Isis, Thonis-Heracleion

I’m pretty sure this is one of the most extensive exhibitions we’ve been to in a long time. It was well worth it, and I’m glad we got the chance to see it.

Statue of Horus protecting pharaoh. The pharaoh shown is Nectanebo II, the last native pharaoh of Egypt. The falcon's eyes were inlaid with glass, but only the left one has remained intact.

It’s hard to grasp the scale of some of the statues when you look at the pictures. It was more than a little daunting standing before them as they towered over us. More than ever now, I want to visit Egypt.

Statues of Ptolemaic king and queen, Thonis-Heracleion. The king's statue is about 16.4ft high; the queen is just over 16ft.