The Sunday Section: Ancient Egypt - Mummification, the Ba, Ka and Akh

Why did the Ancient Egyptians mummify their dead? According to their belief system, an intact body was a fundamental part of a person’s afterlife. By preserving the body, the other important parts that made up a human being were also preserved – the shadow, the name, the ka, the ba, and the akh. All these elements were necessary to achieve rebirth into the afterlife.

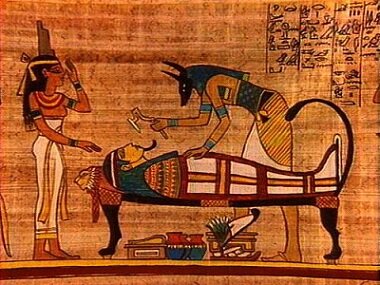

Priests involved in the mummification process wore Anubis masks, Anubis being the patron of funeral rites, among other things

Egyptian mummies were deliberately made by drying the body, moisture being the source of decay. The body was dried using a salt mixture called ‘natron’. Made up of 4 salts – sodium carbonate, sodium bicarbonate, sodium chloride, and sodium sulphate – natron is a natural substance, found in abundance along the River Nile. The drying agent, sodium carbonate, draws the moisture out of the body, while the bicarbonate reacts to the moisture, increasing the pH that creates a hostile environment for bacteria. The whole process was aided by the hot and dry climate of Egypt.

After the body was washed, a cut was made in the left side for the removal of the internal organs. The liver, lungs, stomach and intestines were washed and packed in natron. The heart, believed to be the centre of intelligence, which would be needed in the afterlife, was left in the body. The brain was not thought to be important, and was removed by inserting a long hook up the nose and pulling it out. The body was then covered with natron, which was also stuffed into the body, and was left for 40 days to dry it out. The body was then washed and covered with oils to maintain its elasticity.

Up until about 1000BC, the internal organs, once dried, were placed in Canopic jars. The lids of the jars were represented by the four sons of Horus – Imsety looked after the liver; Hapy, the lungs; Duamutef, the stomach; and Qebehsenuef, the intestines.

Osiris, Isis, Nephtys and the four sons of Horus ready to receive the deceased

(L to R) Imsety, Hapy, Qebehsenuef, Duamutef

Canopic jars

After 1000BC, the embalmers began to return the dried internal organs to the body. But, to symbolically protect the internal organs, Canopic jars were still buried with the mummy.

Once washed, cleaned and oiled, the body was then wrapped in linen, starting with the head and neck. The fingers and toes were all wrapped separately, along with the arms and legs. Amulets were placed between the layers of wrappings to protect the body as it journeyed through the underworld.

Amulets on the body (Image from ‘Ancient Lives, New Discoveries’ exhibition book from the British Museum)

Spells were read as the body was wrapped to further protect the deceased. A papyrus scroll with spells from the Book of the Dead was placed between the wrapped hands. More layers of wrapping were added, glued together with liquid resin. Finally, the mummy was wrapped in a large cloth, which was held together with strips of linen. It was then placed in a coffin, which was placed in a second coffin.

(Image from ‘Ancient Lives, New Discoveries’ exhibition book from the British Museum)

After the funeral, the ‘Opening of the Mouth’ ritual was performed to allow the deceased to eat and drink again. Then the body in its coffins was placed in a stone sarcophagus in the tomb. Around the sarcophagus was placed food and drink, furniture, valuable items and clothing.

‘Opening of the Mouth’ ritual

The wooden sarcophagus of Pa-Kush, priest of Atum - Egyptian Antiquities Hall, Hermitage Museum (Image taken by Andrew Bossi)

With his body preserved, the deceased was ready for rebirth into the afterlife.

Apart from the akh, the other elements were part of a person from birth. The name, given at birth, would live as long as the name was spoken. The shadow was represented as a small human figure, painted black. The ka, represented by two raised arms, was said to be a person’s double, reflecting the Egyptians’ belief in dualism. For lack of a better translation, it is called the ‘life-force’, the spirit or soul. Created at the same time as the physical body, it was made on a potter’s wheel by Khnum, the ram-headed creator god. It did not mean, however, that the ka and the body were inseparable. When the body died, the ka left the body to join its divine creator; the phrase “going to one’s ka” was a euphemism for ‘dying’.

The ka was believed to have the same needs that the person had in life, including eating and drinking. To ensure the continued existence of the ka after the death of the body, offerings were made by the deceased's family. The ka was thought to travel between the ‘magical’ world and the world of the living through ‘false doors’ – funerary stelae shaped like porticos, with magical formulae that listed the offerings the ka received on a daily basis. The ka of gods and kings represented a form of individuality, whereas the ka of the common people were believed to be the ancestors of each family, which were passed from generation to generation. The ka of the king is represented as a small figure wearing the ka -symbol, and the Horus-name of the king on its head. There seemed to be a connection between the Horus-name of the king, and his ka.

The ‘ka’

The ba symbolised the vital principles of human beings; although an exact translation cannot be given, it may mean ‘power’ or ‘force’. The ba entered the person’s body at birth, and left at death, and was able to move freely between the underworld and the physical world. It was represented as a bird, sometimes with a human head, emphasising the mobility of the ba after death. Still it had to return to the body and to the offering tables for the necessary sustenance.

‘letting Ba rejoin its corpse’ - Spell 89 from ‘Ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead’

The akh was “ the transfigured spirit that survived death and mingled with the gods”. It was a person’s soul that had been judged by Osiris, and found Maat Kheru-justified. Like the ka, the akh was believed to need a preserved body, and tomb to exist.

[The deities mentioned here can be found in ‘Ancient Egypt - Gods and Goddesses’]