The Sunday Section: Ancient Egypt - Medicine

Medicine in Ancient Egypt was far more advanced than the sort practiced by witch doctors in primitive tribes. According to Homer in ‘The Odyssey’, “In Egypt, the men are more skilled in Medicine than any of human kind”.

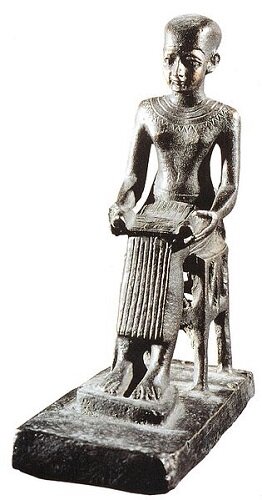

The most famous Egyptian physician was Imhotep, who was also a high priest, a scribe, and vizier to King Djoser.

Imhotep

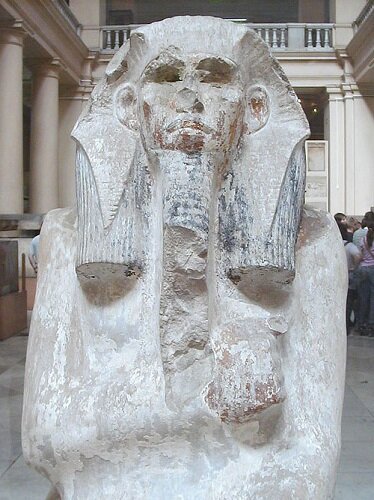

King Djoser

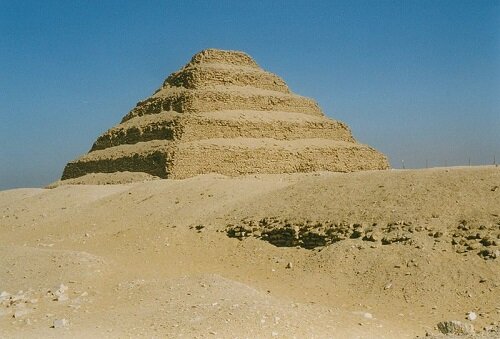

He is probably best known, though, as the architect of the Step Pyramid of Saqqarah, the first pyramid and first structure put together by humans that is made entirely from stone … not quite the way he has been portrayed in the various ‘Mummy’ films.

Step pyramid of Djoser at Saqqara (Image by Arian Zwegers)

Imhotep’s best-known writings were medical text. Although the authorship is debated, he is believed to be the author of the ‘Edwin Smith Papyrus’, chiefly concerned with surgery, named after the dealer who bought it in 1862, it dates to the 16th-18th Dynasties, about 1500BC.

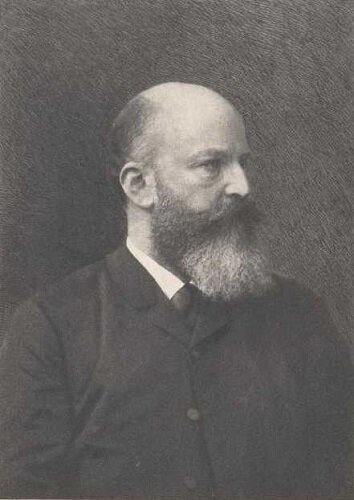

Edwin Smith, American Egyptologist

A scroll just under 5m in length, it describes 48 cases of injuries, with each case detailing the type of injury, the examination of the patient, diagnosis and prognosis, and treatment.

Edwin Smith Papyrus

The medical profession was an extremely organised one, with physicians – swnw (sunu) – managed by the Overseer of Physicians, imy-r swnw; who was in turn managed by the Chief Physician, wr swnw; above him was the Eldest Physician, smsw swnw; then the Inspector of Physicians, shd swnw; and finally, the Overseer of Physicians of Upper and Lower Egypt.

There was also an official ‘Lady Overseer of Lady Physicians’, who supervised the work of female physicians who specialised in minor surgery, bloodletting, obstetrics and gynaecology. The first recorded female doctor was possibly Peseshet (2400BC); on a stela dedicated to her, she is referred to as imy-r swnwt, which has been translated as ‘Lady Overseer of Lady Physicians’ (snwnwt being the feminine of swnw)

As with other prehistoric civilizations, Egyptian physicians believed that healing and religion were inseparable, that different parts of the body were governed by different gods, and so used special religious incantations to treat patients for specific ailments. Unaware as they were of microbiology, physicians thought internal diseases were caused by divine punishment or magic. They would first attempt to neutralise the evil before turning to medical treatment.

Egyptian physicians, however, stood out from those of other civilisations because they kept detailed records of case histories. Interestingly, their texts show medical methods that are very similar to modern medicine, for example, the use of direct compression to stop bleeding.

Another way Egyptian physicians were different was their knowledge of anatomy and physiology, probably because they embalmed their dead, whereas other civilisations burned them. For example, they would have needed to have a good knowledge of the anatomy of the head and brain for the process of emptying the skull through the nostrils by employing a long hook.

Another medical papyrus, the Ebers Papyrus, which contains herbal knowledge, describes the position of the heart precisely. Purchased by Georg Ebers in 1873-74, it contains a ‘treatise on the heart’, and notes that the heart is the centre of the blood supply, with vessels attached for every member of the body.

Georg Ebers, German Egyptologist

A 110-page scroll, about 20m long, it was written in about 1500BC, but is believed to have been copied from earlier texts. Along with the Edwin Smith Papyrus, and 4 other papyri, the Ebers Papyrus is among the oldest preserved medical documents.

Ebers Papyrus

The Edwin Smith Papyrus details the physiology of blood circulation, and its relation to the heart, along with an awareness of the importance of the pulse:

“It is there that the heart speaks”

“It is there that every physician and every priest of Sekhmet places his fingers … he feels something from the heart”

The process of examining the patient, interestingly, is what is used in modern medical practice – interrogation of the patient; inspection, including body discharges; palpation of the pulse and the abdomen – “You should put your finger on it, you should then palpate his belly”; and percussion – “… and examine his belly, and knock on the finger … place thy hand on the patient and tap”.

Following diagnosis, one of three decisions would be made – “An ailment which I will treat”, “An ailment which I contend”, or “An ailment not to be treated” – of the 48 cases discussed in the Edwin Smith Papyrus, only 3 were declared hopeless.

The suturing of non-infected wounds with needle and thread is shown in the Edwin Smith Papyrus. Raw meat was applied on the first day as it is known to be an efficient way to prevent bleeding. This would then be replaced with a dressing of astringent herbs, honey and butter, or mouldy bread. Honey is an effective hygroscopic material, meaning it absorbs water, and it also stimulates the secretion of white blood cells, the body’s own natural defence mechanism. It is fascinating to read that the Ancient Egyptians were using mouldy bread to treat wounds; it wasn’t until 1928 that Alexander Fleming successfully extracted penicillin from mould, a discovery which earned him the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1945.

Mild antiseptics that were used include frankincense, turpentine, date-wine and acacia gum. Surgical instruments, including scalpels, copper needles, forceps, lancets, hooks and probes, were used. Engraved on a wall in the temple of Kom-Ombo, which has a House of Life, is a collection of surgical instruments.

Kom Ombo Temple, surgical instruments (Image © Ad Meskens / Wikimedia Commons)

Excavations of skeletons of craftsmen and builders who worked on the pyramids show limb fractures, mainly of the forearm and leg. Most of the fractures show signs of complete healing with good realignment of the bone, which can only be achieved if they had been set correctly with a splint.

The diagnosis of sciatic pain was described in the Edwin Smith Papyrus:

“If thou examinst a man having a sprain in a vertebra of his spinal cord, thou shouldst say to him: extend now thy two legs and contract them both again. When he extends them both, he contracts them both immediately because of the pain he causes in the vertebra of his spinal column in which he suffers. Thou shouldst say concerning him: One having a sprain in a vertebra of his spinal column”.

This same method is used today to test for sciatic nerve irritation, and is called Lasegue’s sign.

It should, therefore, come as no surprise that medical knowledge in Ancient Egypt had an excellent reputation, with rulers of other empires requesting the use of pharaohs’ best physicians.