The Sunday Section: Ancient Egypt - The Priest

The Ancient Egyptian religion was more than a practice to satisfy the otherworldly needs of the people, it also served as a method to keep society in order, and to preserve the culture. So priests’ duties went beyond caring for the gods and attending to their needs to encompass duties ensuring the smooth running of society, like supervising artists and scribes, teaching at schools, and advising people.

‘Egyptian Priest Entering Temple’ ~ Ludwig Deutsch

The pharaoh was not only seen as a god, he was also the highest of all high priests. Because he could not perform every ceremony at all the temples, he personally appointed high priests to carry out the sacred rituals in his place.

A job of high status, the priesthood included both men and women. They were either chosen by the king, or inherited their post, and were expected to embrace everyday life.

Priests seeing to the deceased

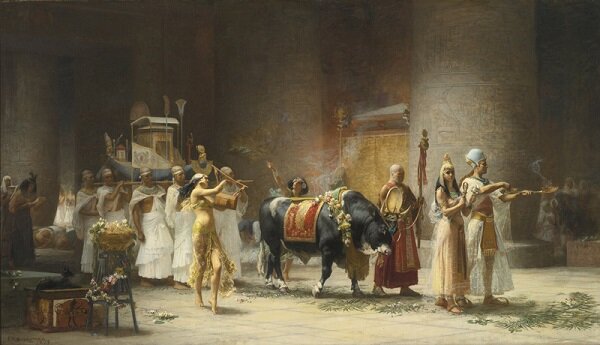

The ‘top-ranking’ priest was the High Priest, or hem netjer. He served the god, taking care of the god and the god’s needs; it was not his job to see to the people’s spiritual needs. He was also known to serve as the Pharaoh’s political advisor. When performing the ritual reading of the sacred texts, the hem netjer used the title kher heb, the ‘lector priest’. He ‘is obliged to read them directly from the papyrus book held open in his hands. He has to recite them exactly as they are written, even if he has read them many, many times before, for making a mistake can offend the god.’ The reading of sacred texts was done at official ceremonies, and at the head of processions, when the god was carried before the people.

‘Apis Procession’ ~ Frederich Arthur Bridgman

The priesthood was divided into 4 groups, with each group entering temple life for 1 month, 3 times a year. For the rest of the year, they were integrated in and out of ‘normal’ society. This system was considered necessary because of the strict purity rites that the priests had to undergo while serving in the temple. Each temple had its own lake where the priests would bathe up to 4 times a day, and from where water was taken for offerings. Priests could not eat fish, as this was thought to be the food of peasants. They could only wear white linen, and sandals made from papyrus; all animal products were deemed unclean. They were also required to shave off all their bodily hair, including the eyebrows, not only for purification purposes, but also to rid themselves of lice. While serving in the temple, they were expected to abstain from sexual activity. However, outside of temple duty, they could marry and raise families.

Book of the Dead papyrus of Pinedjem II 21st dynasty, depicting him in the role of High Priest.

Once purified, the priest was then ready to serve the god of the temple. In the form of a statue, which was believed to contain the deity’s ka, the god was kept in the innermost chamber of the temple, in a shrine called naos. Not always life-sized, the statue could be made of stone, gold or wood, and inlaid with semi-precious stones. Rituals were performed at least 3 times a day.

The god would be woken at dawn by temple singers singing the Morning Hymn. Then the priest would break the seal on the doors to the inner chamber, which would have been tied the previous night, and the doors would be opened. The god would then undergo the same purification process as the priests. As incense burned, the priest would dress the god, and apply perfume and cosmetics. The process was the same as the one which prepared the pharaoh for his day.

Once the god was ready, food and drink would be laid before the statue. The food would, of course, be the best, and included meat, bread, fruits and vegetables, beer and wine. The slaughtering of animals was done away from the sight of the god, for no blood was allowed before the god. Flowers were also included in the offerings. The priest would then pour water over the offerings. Incense, considered to be the ‘perfume of the gods’, was burned in a small pot which was ‘held’ in an open palm attached to a spoon-like saucer, shaped like a forearm.

The offerings were intended to awaken the senses of the gods. Taste was stimulated by the food and drink; sight by the flowers; sense of smell by the incense; and hearing by music and singing. While the god’s ka absorbed the offerings, the musicians, singers and dancers entertained him, mainly by the singing of hymns. The text of the hymns was simple, mainly repetitions of the god’s names and attributes.

There were also priest-magicians who belonged to a ‘House of Life’, an ancient institution of learning, and a holy place.

‘Per-Ankh’ symbol for House of Life; ‘per’ means ‘house’ and ‘ankh’ means ‘life’.

The priests here were considered to be servants of Ra.

Worshipping Ra - image shows a priest pouring water over offerings and holding an incense-burner.

A slaughterer was also part of the community, for the belief was that slaughtering bulls would increase the life force of the place. Conversely, ritually butchering animals thought to embody evil would decrease evil. The House of Life was either part of a temple, or a separate building. Such Houses existed at Abydos, Edfu, Memphis and Akhetaten, to name a few. Though not many have been found, it is thought that larger towns and major temples all had a House of Life.

No descriptions have been found as to the institution’s exact function, but the literary references that there are allude to the storing and production of books, and the teaching of scribes and priests. The House of Life was said to contain secret, magical writings either composed or copied by the priests. These priests were the ones who served the community through counselling, healing, magical arts and ceremony … “the principal subjects studied and practised by the members of the House of Life were medicine, magic, theology, ritual, and dream interpretation …” ~ Miriam Lichtheim ‘Ancient Egyptian Literature’.

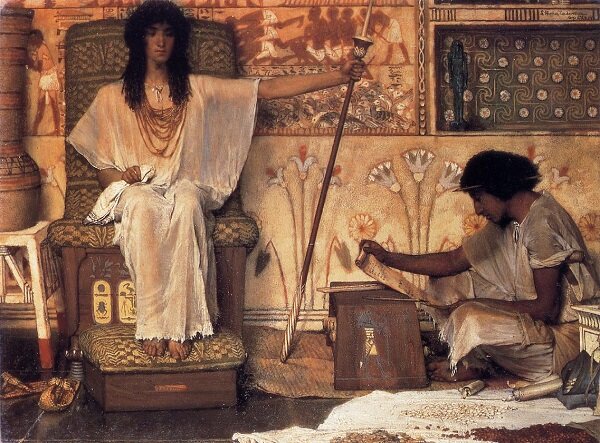

Though not a priest as such, the scribe is worthy of a mention because it was considered the highest of honours to be a scribe in an Egyptian temple or court.

Scribes

So highly prized was the position, not only by the priesthood, but also by the pharaoh, that in some pharaoh’s tombs, the pharaoh himself is depicted as a scribe. Scribes were in charge of keeping vital bureaucratic records, writing magical texts, issuing royal decrees, and keeping and recording funerary rites, especially within ‘The Book of the Dead’.

‘Joseph, Overseer of the Pharaoh’s Granaries’ ~ Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema