Tuesday's Tales - The Victoria Cross in the First World War

What is it that makes a man, finding himself in a nightmare situation the like of which he’s never experienced, go beyond his stated duty and act in a way that will, almost certainly, cost him his life?

The Victoria Cross, the VC, is the highest military decoration awarded for valour “in the face of the enemy”. It is awarded to members of the armed forces of Britain and Commonwealth countries, including territories that were previously part of the British Empire. It may also be awarded to civilians under military command.

In 1854, after almost 40 years of peace, Britain found itself at war with Russia in the Crimean War. Modern reporting brought home and made public many acts of bravery by British servicemen that were going unrewarded. Both, the public and the Royal Court, wanted these gallant acts recognised. A new award came into being which would recognise acts of valour on its own merit, without being influenced by a man’s lengthy or admirable service; neither class nor birth would be recognised.

The medal was intended to be a simple decoration that would be highly prized. To this end, Queen Victoria, guided by Prince Albert, vetoed the initial name for the award – ‘The Military Order of Victoria’ – and, instead, suggested, ‘Victoria Cross’. The VC was introduced on 29 January 1856. The original warrant stated that it would only be awarded to soldiers who have served in the presence of the enemy and had performed some signal act of valour or devotion.

The award is a bronze cross, bearing the crown of St Edward, surmounted by a lion, and the inscription ‘FOR VALOUR’. The first ceremony was held on 26 June 1857, in Hyde Park, where Queen Victoria invested 62 of the 111 Crimean recipients.

In the First World War, the first VC awarded to a British Army officer was to Maurice James Dease – it was awarded posthumously.

Born on 28 September 1889 in Ireland, Maurice Dease was educated at Stonyhurst College, and the Army Department of Wimbledon College; he then attended the Royal Military College at Sandhurst. At the outbreak of war, he was 24 years old, and already a lieutenant in the 4th Battalion, The Royal Fusiliers.

18 days after Britain declared war, on 22 August, Lt. Dease led his men to Belgium. Marching through the city of Mons, the Royal Fusiliers headed to the canal at Nimy, spanned by a railway bridge.

A Company, 4th Royal Fusiliers in the market square of Mons on 22 Aug 1914, the day before the Battle of Mons. Soon after this photograph was taken the battalion moved up to the Mons Canal line at Nimy

Lt. Dease set up his two machineguns on this bridge, not knowing when, or from which direction the enemy would appear. 23 August – the Germans approached, and when some were shot, they regrouped and appeared in lines from different directions.

Nimy Bridge

Amidst intense gunfire and heavy casualties, Lt. Dease was wounded in the leg and neck. Despite this, he climbed out of his command trench and took over the machinegun of a dead soldier. Then the second gun jammed. He crawled down the embankment, got it working, and climbed back to carry on firing.

In his book, ‘The Royal Fusiliers in the Great War’, HC O’Neill wrote: “The machine gun crews were constantly being knocked out. So cramped was their position that when a man was hit he had to be removed before another could take his place. The approach from the trench was across the open, and whenever a gun stopped Lieutenant Maurice Dease … went up to see what was wrong. To do this once called for no ordinary courage. To repeat it several times could only be done with real heroism. Dease was badly wounded on these journeys, but insisted on remaining at duty as long as one of his crew could fire. The third wound proved fatal, and a well deserved VC was awarded him posthumously. By this time both guns had ceased firing, and all the crew had been knocked out …”

The citation for Lt. Dease’s VC: “Though two or three times badly wounded he continued to control the fire of his machine guns at Mons on 23rd August until all his men were shot. He died of his wounds.”

Lt. Maurice Dease is buried at St. Symphorien Cemetery.

.

He is remembered with a plaque under the Nimy Bridge, Mons; in Westminster Cathedral; on a cross in Stroud, Gloucestershire; and a cross at Exton, Rutland. There is also a plaque in St Martin’s Church in Culmullen, County Meath, Ireland. His VC is displayed at the Royal Fusiliers Museum in the Tower of London.

The first VC awarded to a private soldier in the First World War was to Sidney Frank Godley.

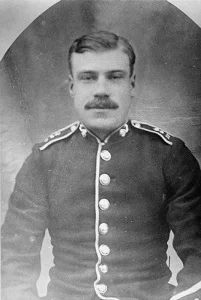

Sidney Godley was born on 14 August 1889 in East Grinstead, West Sussex. After leaving school, he worked in an ironmonger’s store from the age of 14 to 20. In December 1909, he joined The Royal Fusiliers as a private.

A private in the 4th Battalion, Godley was one of Lt. Dease’s men who marched with him to Nimy, and fought with him at the Battle of Mons. When Lt. Dease had been killed, the order to retreat was given. Private Godley volunteered to defend the Nimy Bridge, giving the rest of the section the chance to retreat. He held the bridge while coming under heavy fire and being wounded twice – shrapnel entered his back when an explosion went off near him, and he was shot in the head.

HC O’Neill in ‘The Royal Fusiliers in the Great War’: (continuing from the paragraph above):

“… By this time both guns had ceased firing, and all the crew had been knocked out. In response to an inquiry whether anyone else knew how to operate the guns Private Godley came forward. He cleared the emplacement under heavy fire and brought the gun into action. The water jackets of both guns were riddled with bullets, so that they were no longer of any use. Godley himself was badly wounded and later fell into the hands of the Germans.”

For two hours, Godley defended the bridge until he ran out of ammunition. Dismantling the gun and throwing the pieces in the canal, he tried to crawl to safety but was captured by German soldiers. He was taken to a prisoner of war camp where his wounds were treated, and he remained there until the end of the war.

He had already been awarded the Victoria Cross, and received the actual medal from King George V on 15 February 1919. The citation read: “For coolness and gallantry in fighting his machine gun under a hot fire for two hours after he had been wounded at Mons on 23rd August.”

He got married in August 1919, and worked as a school caretaker in Tower Hamlets, London. He died on 29 June 1957 and was buried with full military honours at Loughton, Essex, where he’d been living.

The first South Asian to be awarded the Victoria Cross was Khudadad Khan.

He was born on 20 October 1888 in the village of Dab in the Punjab, in what is now part of modern Pakistan. A sepoy in the 129th Duke of Connaught’s Own Baluchis, British Indian Army (now the 11th Battalion The Baloch Regiment of Pakistan Army), he was part of the Indian Corps sent to France in 1914, aged 26.

In October 1914, almost immediately after arriving, the 129th Baluchis were among 20,000 Indian soldiers sent to the Western Front. They were to help the exhausted British Expeditionary Force (BEF) prevent the advancing Germans from capturing the important ports of Boulogne (France) and Nieuwpoort (Belgium). If these ports fell into German hands, the BEF would effectively be crippled as they would lose their supply lines.

This offensive to capture the ports, launched by the Germans, was the First Battle of Ypres. On 31 October 1914, the 129th Baluchis were engaged in heavy fighting around the Belgian village of Hollebeke. The conditions were horrific – waterlogged trenches, lack of hand grenades, and a severe lack of soldiers to man the defences; they were outnumbered five to one.

Most of the Baluchis had been pushed back the day before. But two machine gun crews remained. One was Khudadad Khan’s team. They continued to fight, keeping the Germans at bay. The other machine gun was destroyed by a shell, its crew killed or wounded. Khudadad’s team carried on. The British officer, Captain Dill, was severely wounded. Himself wounded, Khudadad Khan kept on firing the gun with the other men until they were overrun; all the gunners were shot or bayoneted. All except Khudadad Khan, who was badly wounded. Pretending to be dead, he waited until the Germans had moved on and, under cover of darkness, managed to make his way back to his regiment.

Thanks to his bravery, and that of his fellow Baluchis, the Germans had been stopped long enough for Indian and British reinforcements to arrive. The line was strengthened and the German army prevented from reaching the ports.

The 129th Baluchis fought in several other battles during the First World War; of the 4,447 men who served in the Regiment during the war, 3,585 were lost.

Sepoy Khudadad Khan was treated for his wounds and recovered. Three months later, he was awarded the Victoria Cross by King George V. His citation reads: “On 31st October 1914, at Hollebeke, Belgium, the British Officer in charge of the detachment having been wounded, and the other gun put out of action by a shell, Sepoy Khudadad, though himself wounded, remained working his gun until all the other five men of the gun detachment had been killed.”

Khudadad Khan returned to the Punjab. He died on 8 March 1971. His VC is displayed at his ancestral house in Dab, Pakistan.

Khudadad Khan’s actions and that of his fellow Baluchis are, for me, real food for thought, especially with the ‘me-me’, selfish attitude that seems to pervade society in general, in most parts of the world. Here were men, part of a colonised nation, dying for a king they had never seen, for a cause that had been thrust upon them … they were prepared to put their lives on the line unquestioningly.

In fact, all those who faced the enemy and died, who put their lives on the line, defending their fellow soldiers, ultimately giving their lives for their king and country, for the freedoms we take for granted today … Named and unnamed, they are true heroes. It seems a shame that that freedom now, in a way, allows the existence of that ‘me-me’ attitude.