Tuesday's Tales - The Tale of the War Horse

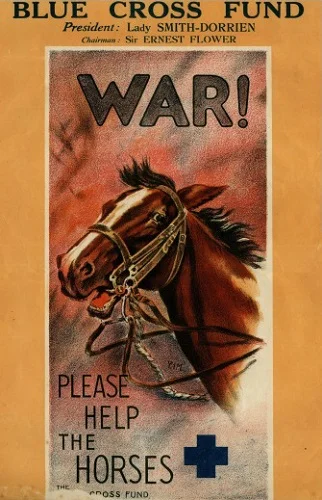

This year marks the 100th anniversary of the start of the First World War, with events, this week in particular, marking Britain’s entry. There will be no shortage of ceremonies to remember the sacrifices made, and horrors that were endured, especially, by the young men of that generation; and quite rightly so. But I don’t know how many ceremonies there will be to remember the sacrifices made, and horrors endured by the animals … the cavalry horses, the pack horses and mules that suffered alongside the men; not forgetting the dogs and pigeons. This is my very small contribution to commemorate their efforts.

Battlefield pigeon, Cher Ami

Messenger dogs and their handlers, France

Most of the information I gathered from a programme, ‘War Horse: The Real Story’, presented by Mark Evans, and featuring experts, Richard van Emden and David Kenyon; and also from ‘History Today’.

In peacetime, despite being totally reliant on horsepower, the British Army only kept about 26,000 horses. So, in 1914, when the army had to mobilise for war, an additional 100,000 horses had to be found. This turned out to be an easy exercise, thanks to a census which the police did every winter – this informed the army of the location of every horse in the country. In the space of a mere two weeks, the army had acquired an astonishing 140,000 horses. This was, obviously, good for the army, but devastating for the businesses and farms that relied on their horses … not to mention heart-breaking for those who looked on their horses as family.

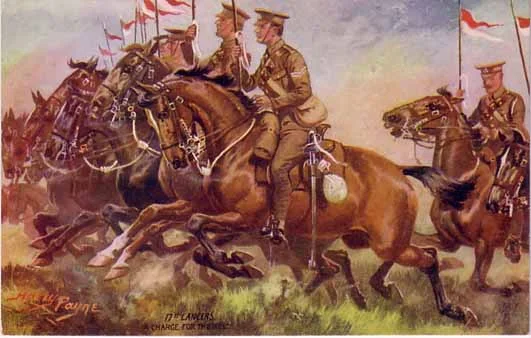

A good deal more recruits volunteered for the cavalry than for the infantry; with its romantic public image, the cavalry was seen as more exciting. The trouble was, many of these recruits were city boys who had never ridden a horse. Not only did they have their work cut out learning how to ride – the army’s method being to keep falling off until you figured it out – these young men, armed with Lee Enfield rapid fire rifles, were also trained to be excellent marksmen. Because of the mobility afforded to them by their horses, the cavalry was expected to fight behind enemy lines. The cavalry’s sabres were replaced with more lethal straight swords – imagine the power behind the sword of the soldier mounted on a 1000lb horse, galloping at a speed of about 25 to 30 miles an hour … that sword would go right through his target.

17th Lancers advancing

For the horses, used to living on farms and in stables, their first real trial was the sea crossing. Pushed and pulled, they were loaded onto the boats, even put in canvas slings and winced on board. Not all of them made it – terrified horses that managed to break free jumped into the sea … with no way to rescue them, the men could only watch helplessly as the boats moved farther and farther away …

In the words of Signaller Jim Crow, 100th Brigade, Royal Field Artillery: “We knew what we were there for; them poor devils didn’t, did they?” There was no way to prepare the ‘poor devils’ for the stress of long distance transport, the endless hours in harness pulling heavy loads … no way to make them understand that they would be shot at, bombed … that they would suffer cold, hunger, exhaustion …

By the end of August 1914, overrun by the Germans in Belgium, the British Expeditionary Force (BEF), was in retreat. As they headed south, the cavalry acted as a protective shield, engaging and delaying the German infantry. All through the retreat, the horses still had to be fed and watered; not surprisingly, they usually went without water. Lack of food and water led to many horses losing weight and condition, with holes having to be punched in the leather girths to keep the saddles on.

As the armies settled in for trench warfare, which had little use for the cavalry, cavalrymen were ordered to dismount and fight alongside the infantry. The horses were used for transportation. With few mechanised vehicles, the role of the horse was as vital as ever. Still, danger was ever-present on the roads to the front line that were under constant shelling; they still had to traverse those roads to get supplies to the soldiers.

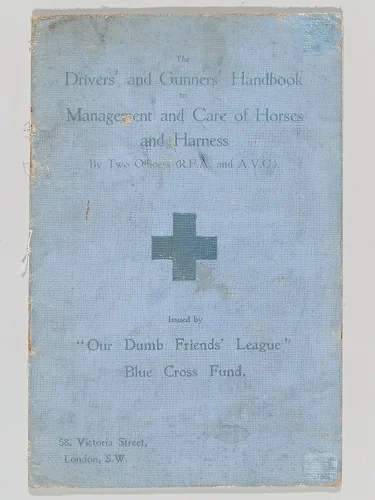

At the end of each day, before he could rest, the driver had to see to his horse first. Many of these men had never cared for a horse before, and found the handbook that the Blue Cross had helped to publish – ‘The Drivers’, Gunners’, and Mounted Soldiers’ Handbook on the Management and Care of Horses and Harness’ – invaluable. Because of the circumstances they were in, man and horse invariably formed a special bond.

Towards the end of June 1916, the cavalry was reformed, ready for the Battle of the Somme. About 50,000 horsemen took up position 5 miles north of the River Somme, ready to follow the infantry. In the week leading up to the 1st of July, over 1.5 million pounds of artillery had pummelled the German frontline positions. Expecting that the defences had been destroyed, the allies’ were expecting an easy victory. Too late, they discovered the German defences were still intact; in the worst day in British military history, the British suffered over 57,000 casualties, with almost 20,000 dead. Despite their readiness to engage the enemy, the cavalry was stood down. From then until the end of the offensive in November 1916, this frustrating pattern of taking up position only to be stood down, was repeated too many times.

Horses were lost due to enemy fire … enough soldiers’ memoirs speak of the awful, heart-wrenching screams of injured, dying horses. DWJ Cuddeford, an officer of the Highland Light Infantry, wrote how, in April 1917, he and his men “put bullets into the poor brutes” crashing through the battlefield in agony, following a German bombardment that had destroyed a British cavalry unit holding the village of Monchy, near Arras.

And yet, more horses died from exhaustion, disease and exposure to extremes of weather. Behind the lines, the veterinary corps carried out vital work, treating about 2.5 million animals. Horses were treated for debilitation, mud fever, shrapnel and bullet wounds, foot injuries, mange … There were no antibiotics, but there was chloroform, which meant that surgery could be performed. Also, mild disinfectant proved successful in the continual flushing of wounds. Amazingly, given the conditions the vets were working under, 80% of the animals treated by the corps recovered and were able to return to duty. Even so, the relentless strain of warfare took its toll; many horses grew listless and uninterested in their surroundings, to the point of refusing food.

Treating a wounded horse

As the war dragged on, despite the appearance of more vehicles, it was still the horse that kept the army mobile and supplied. The heavy horses – the Shires, the Clydesdales, and Percherons – pulled the largest guns and the heaviest wagons. Lighter horses and North American mules hauled ammunition, rations and equipment to the front line. When the supply of horses from Britain ran low, the British purchasing commission turned to the United States and Canada. Throughout the war, practically every other day, a cargo of about 500 American and Canadian horses and mules sailed for Europe.

Horse-drawn artillery wagon, Battle of the Canal du Nord

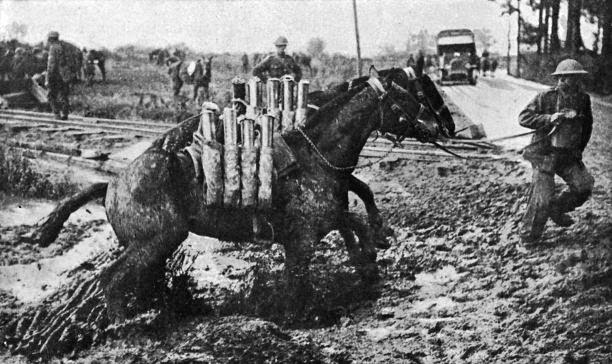

Pack horses carrying ammunition in Flanders

Leading up to July 1917, preparations were being made for the Third Battle of Ypres, or ‘Passchendaele’, as it was more popularly known. The land where the battle was fought had, and still has, a tendency to retain water. This was made worse by the constant bombing which had destroyed the drainage systems. Supplies and equipment still had to get across to the front, but vehicles could not be used, neither could wagons and heavy horses – these would all sink in the glue-like mess that the ground had been transformed into. It was down to the mules and pack horses to transport the necessary items. Tracks were laid on the glutinous ground, and the animals had to be led across them. If they stumbled off the tracks, there was little hope of getting them out, especially in the dark. Heart-breaking photographs show mules chest deep in mud, with teams of men desperately trying to pull them out, spending up to 12 hours battling, in vain, to free them … if the poor beasts didn’t die from exhaustion, the only way to ‘free’ them was with a bullet.

Mules stuck in mud

But having to kill their horses or mules was, for many of the men, ‘beyond the call to duty’; they’d developed too close a bond with their charges, and it was akin to putting a bullet through the head of a friend. So officers were given instructions on the best way to dispatch a horse, which was found in the “Field Service Pocket Book 1914” that every officer carried.

'Goodbye Old Man' - Fortunino Matania

In March 1918, the Germans launched their Spring Offensive, a series of lightning attacks that broke through the British lines and sent them into a fighting retreat. By 30th March, an advanced German division had occupied Moreuil Wood, a hilltop position 5 miles from the strategic town of Amiens. This put them within striking distance of the railway line below, which meant they would be able to drive a wedge between the British and French armies.

The Canadian Cavalry Brigade, under the command of Brig-Gen. JEB ‘Galloper Jack’ Seely, astride his brave thoroughbred, Warrior, were given the order to stop the Germans. Seely ordered a section to seize the northeast corner of the wood; the squadron under the command of Lt. Gordon Flowerdew (of Lord Strathcona’s Horse) was ordered to the southeast corner. The other squadrons were to enter the wood from the northeast.

Brig-Gen. Seely astride Warrior

Despite being taken by surprise, the Germans opened fire. Men and horses fell; still the cavalry charged on into the woods. Vicious hand-to-hand fighting broke out. Six squadrons of cavalry were now in the woods, and Flowerdew was ordered to cut off the retreating German forces. At the northeast corner of the woods, Flowerdew and his men encountered a retreating German force, 300-strong. The lieutenant ordered his men to charge. Riding straight into heavy fire, Flowerdew was mortally wounded, and more than half his men were killed.

The cavalry charge had had the desired effect – by day’s end, having suffered 305 casualties, the wood was in Allied hands. Lt. Flowerdew was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross, one of 20 awarded.

Lt. Gordon Flowerdew

'Charge of Flowerdew's Squadron' - Alfred Munnings

The Allied forces launched their counter-attack in the summer, and finally broke through German lines. By now, modern technology – tanks and planes – were being used in operations, but the horse, as yet unmatched in pace and mobility, still had an important role to play. With the front line becoming more fluid and mobile, the cavalry were finally free to push the Germans back over open country, to engage in skirmishes and scouting missions …

By the end of the war, the British army could only afford to keep about 25,000 of the youngest and fittest horses. About 85,000 of the oldest, and most worn out horses were butchered, to feed the starving French population, and German prisoners. Even the skin and bones were sold to help pay for the war. About ½ million horses were sold to French and Belgian farmers to help them rebuild their war-damaged land. And around 60,000 were taken back to Britain to be sold at auction. Among them was a team of black horses, known as the ‘Old Blacks’; amazingly, they had survived the war together, and were given the honour of pulling the carriage of the Unknown Warrior to his last resting place at Westminster Abbey.

Coffin of the Unknown Warrior; carriage pulled by the Old Blacks

After the war, as the army became more mechanised, the horse began to lose its importance. Of the 17 cavalry regiments that fought in France and Belgium 100 years ago, all that remains today is the Household Cavalry Regiment.

It seems a shame that more isn’t done to remember the efforts of these courageous horses, and other animals, that served alongside the men and women who fought in the First World War … that their sacrifices have somewhat faded from memory. I believe it does them, and us, a huge disservice to allow them to become nothing more than a footnote in the pages of history.