Tuesday's Tales - Assassination, a real-life tale

It is a well-known fact that the assassination of the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, was instrumental in the outbreak of the First World War. But what about the man himself?

Archduke Franz Ferdinand

Emperor Franz Josef

Franz Ferdinand was the nephew of the Austrian Emperor Franz Josef, and, being third in line, wasn’t expected to succeed to the throne. But all that changed when the emperor’s son, Crown Prince Rudolph, committed suicide at Mayerling in 1889. Ferdinand’s father, the emperor’s younger brother, then renounced his succession rights, before dying of typhoid fever in 1896. The 26-year-old army captain found himself heir presumptive to the Austro-Hungarian throne.

Ferdinand’s life became one that was highly regulated as he was groomed to rule a vast nation, which was home to numerous ethnicities. Considered an eligible bachelor, he must have been aware of the very strict rules that governed the Hapsburg monarchy – only members of a reigning or formerly reigning European dynasty were considered suitable marriage partners.

Yet this didn’t stop him falling in love with a lady-in-waiting to a member of a Hapsburg relation. Sophie Chotek von Chotkova was a member of a Bohemian aristocratic family, but she didn’t fit the criteria. Ferdinand courted Sophie secretly for about two years, mainly through letters. When their courtship was discovered, Sophie was dismissed, and Ferdinand declared his love for her, vowing that he would marry only her and no other woman.

A furious Emperor Franz Josef refused to agree to the marriage as he believed Ferdinand was marrying beneath his station. But, in the end, he relented when Pope Leo XIII, Tsar Nicholas II and Kaiser Wilhelm II intervened on Ferdinand’s behalf. The Emperor insisted on one condition – Ferdinand had to agree to a morganatic marriage. Usually concerning royal marriages, this is a marriage between those of unequal social rank, and prevents the passing of the husband’s titles and privileges to the wife and their children. This meant that Sophie would not have royal status, was not allowed to accompany her husband to any official function, and their children’s rights of succession were renounced. They married in 1900; the emperor, and most of the royal court, refused to attend.

Franz Ferdinand and Sophie

For all that they’d given up, theirs was a very rare example, for that time, of a royal love marriage that worked. Their life couldn’t have been made easy by the arrogant, close-knit Austrian monarchy and aristocracy. Sophie’s position at court was humiliating, for all the archduchesses, princesses and countesses of Austria and Hungary took precedence over her, even if they were children. And, despite Ferdinand being the heir presumptive, protocol problems meant many royal courts were prevented from hosting the couple.

Understandably, Ferdinand and Sophie spent very little time, if any, at the official residence, Belvedere in Vienna. Instead they preferred to stay at Konopiště Castle, in Czechoslovakia, which Ferdinand had bought. There the happily married couple spent their days with their three children – Sophie, born in 1901; Maximilian, born in 1902; and Ernst, 1904. A contented husband and devoted father, Ferdinand’s private persona was very at odds with the public’s perception of him – he was deemed unpopular because of his short temper, lack of culture and mistrusting nature.

Konopiště Castle

Ferdinand’s unpopularity was mainly due to his radical ideas for political reform. His emperor-uncle, on the throne since 1848, was stubbornly resistant to change. The way the political system worked allowed Austrians and Magyars to dominate government. But Ferdinand realised that restricting what little power the national minorities had within the empire would only cause them to seek help from other countries, thus undermining the empire’s power … “I can’t help being surprised that there is any loyalty left among the nationalities after their treatment for so many years past. I must have them with me. This is the only salvation for the future.”

He believed that political reform was the best way to preserve the multi-national Austro-Hungarian Empire, and to protect his own future as emperor. He planned to combine the Slavic lands within the empire, thereby giving them a voice in government equal to that of the Germans and Austrians.

He also wanted to avoid war in the Balkans … “To peace. What would we get out of war with Serbia? We’d lose the lives of young men and would spend money better used elsewhere. And what would we gain for heaven’s sake? A few plum trees, some pastures full of goat droppings and a bunch of rebellious killers.”

As Inspector General of the army, Franz Ferdinand was invited by General Oskar Potiorek, the Governor of Bosnia, to inspect the imperial armed forces in Bosnia-Herzegovina. The annexation of these former Ottoman territories by Austria-Hungary in 1908 had fuelled the indignation of Serbian nationalists who believed these territories belonged to the newly formed Serbian nation.

The date chosen for Ferdinand’s visit – June 28 – was one of great importance to Serbian nationalists; it coincided with the anniversary of the First Battle of Kosovo in 1389, in which medieval Serbia suffered defeat at the hands of the Turks; on that same day, a Serbian knight, Miloš Obilić, killed the Ottoman sultan, Murad I. The Serbian ambassador to Vienna warned against visiting on that day, a natural focus for revulsion against such a potent display of Austrian imperial strength. But the ambassador’s warning was ignored.

Because of Emperor Franz Josef’s displeasure concerning Sophie and her lack of royal status, she was not allowed to accompany Ferdinand to any official functions. In Bosnia, however, Sophie was able to appear beside Ferdinand at official proceedings because, being an annexed territory, Bosnia had limbo status.

It’s generally agreed that the ‘Black Hand’ organisation was behind the assassination, the major motivation being to stop Ferdinand’s proposals, which would undermine Serbian nationalism. They recruited and armed the young men who were to carry out the assassination. The men had no trouble sneaking into Bosnia as they were helped by members of the Serbian Border Guard. Alarmingly, the Chief of Serbian Military Intelligence was himself a member of the Black Hand. Even more chilling – the assassination had been planned with the knowledge and approval of the Russian ambassador and the Russian military attaché, both in Belgrade.

Amid barely any security, the Archduke and Duchess rode in the motorcade on their way to Sarajevo Guildhall. A bomb was thrown by Nedeljko Čabrinović; it rolled off the back of the car and wounded an officer and some bystanders. Arriving at the guildhall unhurt but understandably stressed, Ferdinand berated the mayor.

Nedeljko Čabrinović

Franz Ferdinand and Sophie emerging from Guildhall

Afterwards, Ferdinand and Sophie abandoned their planned programme, deciding instead to visit the hospital where the wounded from the bombing had been taken. Unfortunately, in the confusion of the moment, the driver of the royal car hadn’t been told of the change of plans and the new route. Instead of carrying directly on along Appel Quay, the driver mistakenly turned right onto Franzjosefstrasse. On being told of his error, he tried to turn the car around, but it was a big car to manoeuvre on a fairly narrow street.

The Gräf & Stift royal car

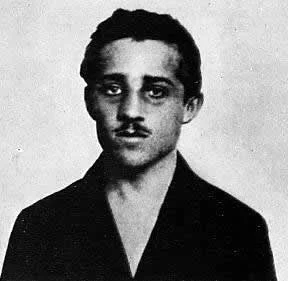

Gavrilo Princip

Bizarrely, one of the assassins, 19-year-old Gavrilo Princip, believing the assassination attempt had failed after Čabrinović had been arrested, had stopped at Schiller’s shop on that very street on his way home. Coming face to face with his target, he walked up to the car and fired, hitting Ferdinand in the jugular. Following a tussle, he fired again, shooting Sophie in the abdomen. An angry mob attacked Princip who was dragged away by police. Later he said that his target had been Potiorek, not the Duchess. Both Ferdinand and Sophie died before they reached the hospital.

The funeral was held on July 4th, in Vienna. Even in death, Franz Josef could not set aside his prejudice and hatred. With his agreement, his chamberlain organised the funeral so that the majority of foreign royalty, who had planned to attend, were dissuaded from doing so by being told that it was only for the immediate imperial family; even the dead couple’s three children were excluded from the public ceremonies. The officer corps were forbidden to salute the funeral train, and public viewing of the coffins was strictly limited. Because Sophie could not be buried at the Imperial Crypt, she and Ferdinand were buried in a crypt beneath the chapel of his castle, Artstetten. Franz Josef did not attend the funeral.

Arstetten Castle

In Austria-Hungary, the assassination was seen as Serbia’s declaration of war on the empire, and calls were made for Austria-Hungary to take revenge on Serbia. Because Serbia could count on Russia’s assistance, a declaration of war was delayed by Austria-Hungary while assurances of support were sought from the German leader, Kaiser Wilhelm. If Russia decided to step in, it wouldn’t simply be a case of Austria-Hungary squaring up against one country, for Russia had allies of her own – France and Britain.

On July 28th, Austria-Hungary, with Germany’s support, declared war on Serbia. The fragile peace between Europe’s great powers began to crumble. Within a week, Austria-Hungary and Germany were facing off against the combined might of Russia, Belgium, France, Britain and Serbia, heralding the start of the First World War.

How ironic that in life, Franz Ferdinand had been a champion of peaceful co-existence with Serbia, yet in death, he had unwittingly become a cause for war.