Chepstow Castle, Tintern Abbey

Treated myself to my third outing this weekend just gone. I’d been given a book, ‘The Greatest Knight’, about William Marshal, who’d lived from 1147-1219. Considering how great a knight he was, so little is known or written about him. The book (fiction) is by my favourite historical writer, Elizabeth Chadwick, and she’s fleshed him out in a believable way. Marshal’s wife, Isabel of Clare, was the heiress of Striguil; while reading the book, I wondered where in England that had been. In the notes at the end, Ms Chadwick mentioned that Striguil was the medieval name for Chepstow, on the Welsh side of the border with England. Which means that Chepstow Castle was Marshal’s through his marriage. And that’s where I went for the weekend. As the train journey took about 5 hours, I knew I wouldn’t be doing it as a day-trip.

For a small-ish town, Chepstow was heaving with people. Found out from a very chatty taxi driver the next day that Mr Tom Jones had played a concert at Chepstow Racecourse Saturday night; his presence had almost doubled the number of the town’s inhabitants! I stayed in a pretty little hotel, which had a view of the castle. The people were friendly, the town clean, and wore its long history with pride.

The hotel I stayed at is a little to the left of where I stood to take this picture

Chepstow Castle, despite its age, is still a magnificent building, standing on tall cliffs overlooking the River Wye. Built in 1086, it was one of numerous castles built to secure the border, or March, between England and Wales. The castle remained in royal hands until about 1115, when it was granted to Walter fitz Richard of Clare. When his son, Earl Richard, better known as ‘Strongbow’, the conqueror of the Irish province of Leinster, died, and his son after him, the castle passed to Earl Richard’s daughter, Isabel. Because of her young age, she was made a ward of King Henry II, and was considered one of the greatest heiresses in the country. As a reward for Marshal’s unswerving loyalty, the king promised his young ward to the knight in marriage; they were wed in 1189.

William Marshal effigy, Temple Church, London

By the time the castle passed into Marshal’s possession, it was old. Marshal went about creating a formidable, yet comfortable castle. When Marshal died, each of his five sons inherited the castle, and it remained in the family until 1245. After that date, because there were no surviving male heirs, Chepstow passed to Marshal’s eldest daughter, Maud, who had married Hugh Bigod. Her son, Roger Bigod, 4th earl of Norfolk, inherited her share of the Marshal inheritance, including the title of Earl Marshal and Chepstow Castle. This then passed to Roger’s nephew, another Roger, and on his death, the castle and his lands were back in royal hands, starting with Edward I.

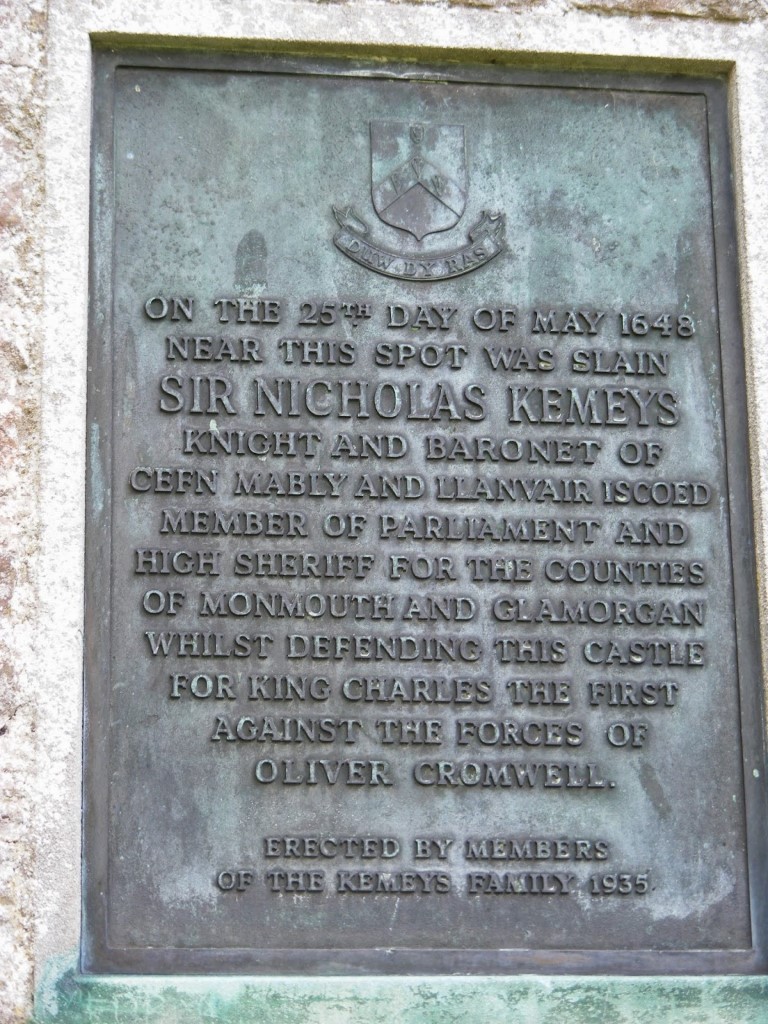

In 1642, at the start of the Civil War, the castle’s owner, Henry, the 5th earl of Worcester, declared for King Charles I. The castle, strategically placed at the entrance to South Wales, controlled the Severn estuary and its links to the important royalist stronghold of Bristol. It was only when Bristol fell in 1645 that the parliamentarians were able to force the surrender of the castle. In 1648, after Charles I had been captured, diehard royalists instigated the second phase of the Civil War through a number of uprisings. The royalist, Sir Nicholas Kemeys, tried to defend Chepstow Castle with 150 men. But the parliamentary forces “razed the battlements, destroyed the garrison’s guns and bombarded the interior with mortar shells.” The garrison surrendered, and Sir Kemeys was peremptorily shot. Chepstow Castle was granted to Cromwell, and it was converted into a military barracks, and a prison for political dissidents.

During the 18th century, parts of the castle were used, among other things, as a nail manufactory. In the 19th century, the 8th duke of Beaufort cleared out the interior of the castle, making it more welcoming by adding paths and seats. In 1953, the owners, the Lysaght family, put the castle in the guardianship of the State; it is now maintained by Cadw, the historic environment service of the Welsh Assembly.

One thing about this castle ... it's very sprawling, unlike Bodiam Castle, which with its 'compact' design, was easy to work out what was what. With Chepstow Castle, it was a case of walking from one area to another, and it wasn't readily obvious what the function of each part of the castle was.

The River Wye

Leading down to the cellar

These are the oldest castle doors in Europe; dendrochronology (tree-ring dating) was used to establish their age - they were made no later than the 1190s

Roger Bigod's great hall, looking towards the service rooms; the stairs lead up to his chamber which was closed off

This looks like an original piece of timber

The great tower

The interior of the great hall, in the great tower

Remembered to take a picture of castle steps ...

More steps ... I was taking these one at a time

Marshal's Tower

After I checked into the hotel, I went for a walk around the town and stopped for a bite to eat. Back at the hotel, I noticed the garden at the back and decided to sit for a while. I think there was a wedding party at the pub next door with live music – I’m pretty sure I could make out violin, guitar, cello and piano, playing Beatles songs … interesting hearing them rendered in an almost classical way.

On Sunday, I visited Tintern Abbey, about a 10-minute taxi ride away. William fitz Richard of Clare was responsible for the foundation of this Cistercian monastery in 1131. When William Marshal became lord of Chepstow, he also became patron of Tintern; his heirs continued to support the abbey. His wife, Isabel, two of his sons, Walter and Anselm, and his daughter, Maud, are buried there.

The abbey was surrendered to King Henry VIII’s visitors in September 1536 during the first stage in the suppression of the monasteries, a process that continued through to 1540. The buildings and its border possessions were granted to Henry Somerset, earl of Worcester. He and his successors leased out parcels of land; makeshift cottages and early industrial buildings sprouted up amongst the ruins.

Tintern lay, more or less, forgotten until the late 18th century when it was discovered by artists, such as JMW Turner, and poets like William Wordsworth; interest in the ruins grew. In 1901, Tintern, deemed a monument of national importance, was purchased by the Crown, and work was undertaken to repair and maintain the fragile ruins. Now, like Chepstow Castle, the abbey is looked after by Cadw.

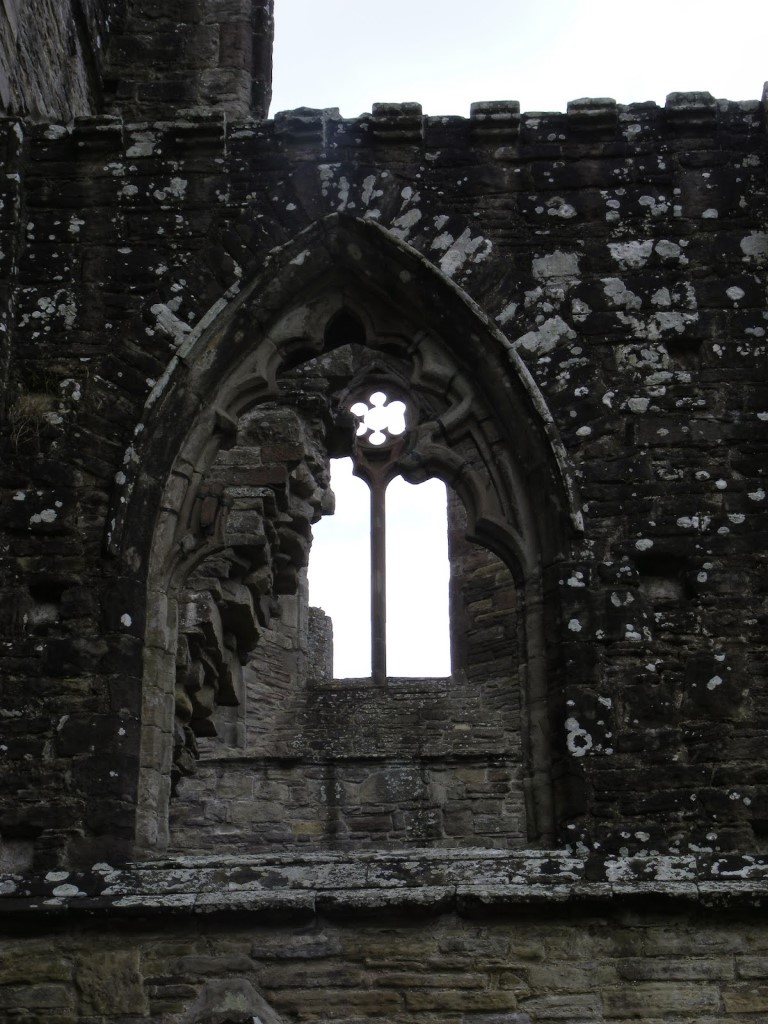

Strangely, the abbey looks small when seen from the road; even the photo on the official guide makes it look small. It’s only when you stand inside the ruins do you get a sense of its great size. When I take pictures of places like this, I always try and get shots that don’t include people; but this time I’m glad I’ve got some with a couple of people as it gives an idea of how immense the building is. I especially like the contrast of columns and archways …

Close-up of the door that can be seen in the middle-left of the photo above this one

Again, the weather turned out brilliant. And again, another perfect weekend away, pleasantly wonderful in so many ways … hard to believe I can be so blessedly lucky :)