Favourites on Friday - Mammoths at the Natural History Museum

Boys and I were in London yesterday, for the ‘Mammoth’ exhibition, which was incredible.

It was well laid out, and, better still, wasn’t heaving with loads of people; it was busy but manageably so. And the best part – photography was allowed, but not flash photography – the reason why the pictures aren’t that good – and no pictures were allowed of the baby mammoth. It took us just over an hour, but we weren’t rushing it, and spent time just gazing at the displays.

A little introduction … Mammoths aren’t ancestors of elephants; they’re close relatives and belong to the same family, Elephantidae. About 6 million years ago, a branch of Elephantidae split into 3 groups – Mammuthus, the earliest mammoths, Loxondota, the ancestors of today’s African elephants; an Elephas, the ancestors of today’s Asian elephants.

Mammoth femur (thigh bone) – just over 3 feet and weighs 88lb; by comparison the femur of a 5.9ft tall adult human is about 1.5 feet and weighs just over 4lbs.

Bronze statues from the tiny, pig-like Moeritherium, through the mammoths, to the pygmy mammoth, to the African savannah elephant.

Complete skulls of Moeritherium are rarely found; this cast is a composite of a cranium and lower jaw from two different Moeritherium specimens.

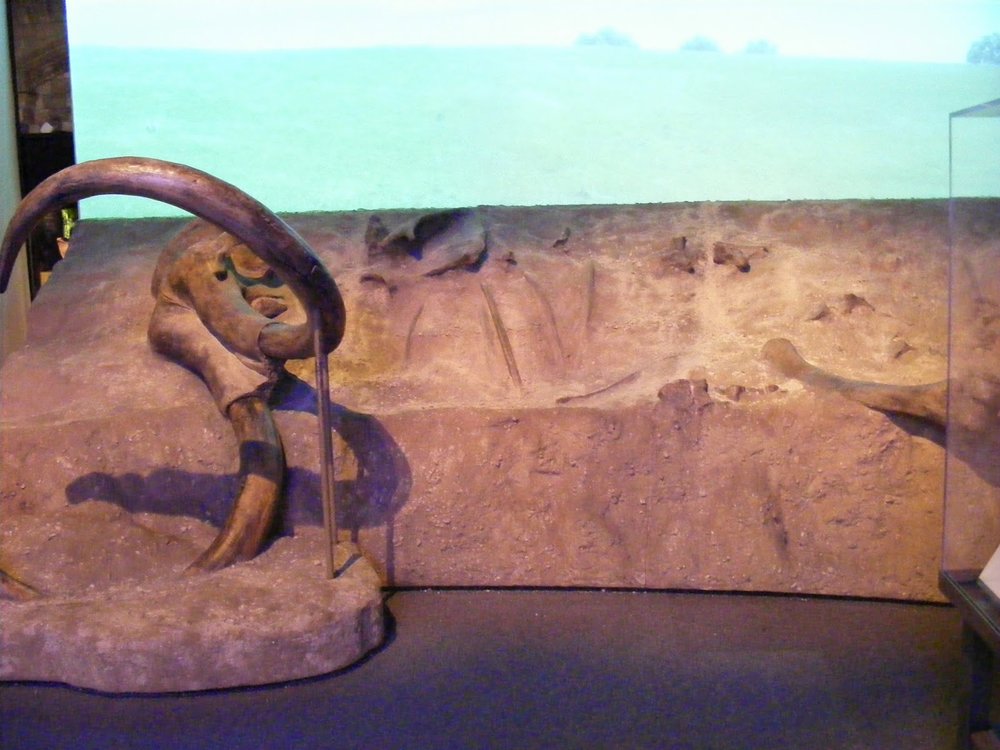

Deinotherium, probably the largest of the ancient proboscideans (order which encompasses trunked mammals) – showing the upper jaw. It’s most distinctive feature were two elongated lower incisors forming downward-curving tusks.

Amebelodon’s most distinctive feature was its lower tusks, which were narrow, elongated and flattened; it's popularly called a ‘shovel-tusker'.

Gomphotherium had 2 pairs of tusks, upper and lower. The upper tusks curved downwards, while the lower tusks could be more than a metre in length.

In response to their increasingly cold habitat, woolly mammoths evolved thick layers of fat beneath their skin. Over this, they had a warm undercoat of fur, and an overcoat of guard hairs, which protected them against the wind.

(International Mammoth Committee/Francis Latreille)

The undoubted star of the exhibition – 42,000-year-old baby mammoth, Lyuba, the most complete and best-preserved mammoth discovered to date. She was found, preserved in the frozen Arctic soil, in 2007 by a Siberian reindeer herder. She was named ‘Lyuba’ after the herder’s wife. This little baby, only about a month old when she died, is amazingly well preserved – wrinkles on her skin are still visible; her eyes and internal organs are intact; hairs are still visible on parts of her body and tail. About 45 inches long, she weighs about 100lbs. Sadly, she died of suffocation after being trapped in mud by a riverbank. Silt filled her trunk and her body was quickly covered by sediment, which effectively sealed off oxygen. Even though she lay exposed for almost a year before her discovery, she is so well preserved because of a lactic-acid-producing bacteria that colonised her body after death. This had the effect of ‘pickling’ her soft tissues and, along with the freezing, kept her in excellent condition.

Even the study of her teeth reveals so much – the development of her baby teeth indicates how long she spent in her mother’s womb, about 22 months, which is the same as in elephants; isotope analysis confirmed she was born in early spring; tooth growth stopped when she was about a month old, indicating that is when she died.

Studying her well preserved internal organs revealed milk from Lyuba’s mother, pollen from grasses and other plants, algae from lake water, and mammoth dung – apparently, mammoths did the same as elephants do now – feed dung to their calves to introduce bacteria that will help digest plants.

Woolly mammoth tusks – larger and more spiral in form compared to elephant tusks. The ones here are just over 6.5 feet in length. The world record woolly mammoth tusk measures over 13 feet long.

Colombian mammoths had high dome-shaped skulls like woolly mammoths; their tusks weren’t as spiral-shaped but were much larger.

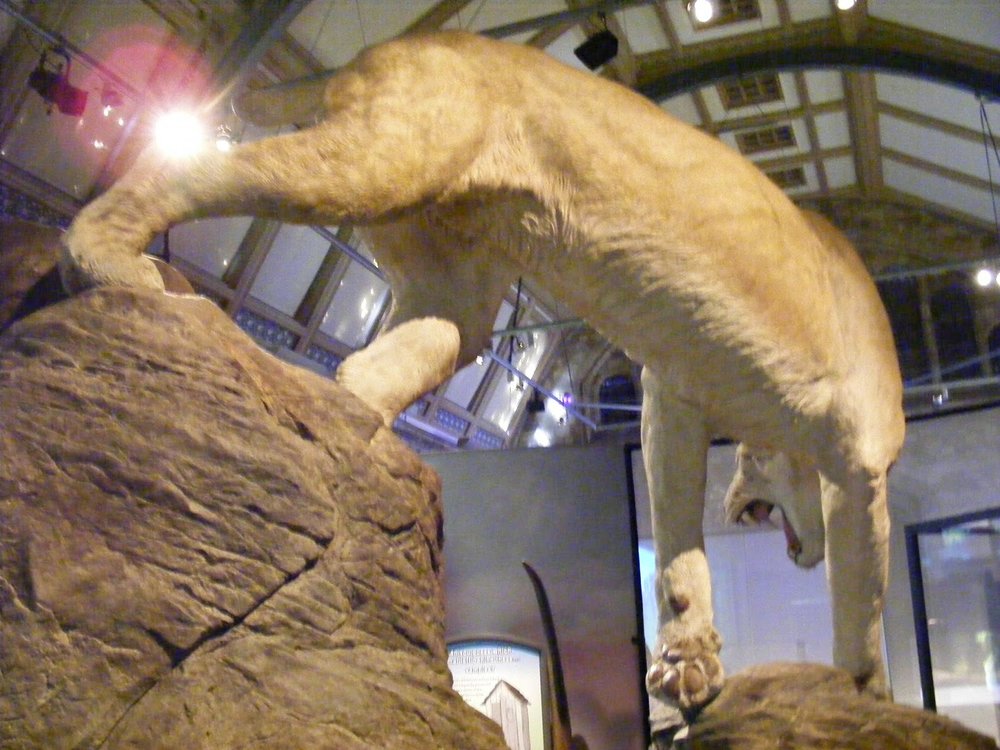

Short-faced bear – fast and formidable, this giant bear stood just over 11 foot on its hind legs, making it the largest carnivore in North America during the Pleistocene Ice Age.

Bronze cast from the skull of a short-faced bear.

Bronze cast created from the skull of a sabre-toothed cat found in Friesenhahn Cave, Texas, where researchers discovered 32 skeletons of sabre-toothed cats along with hundreds of teeth of juvenile mammoths.

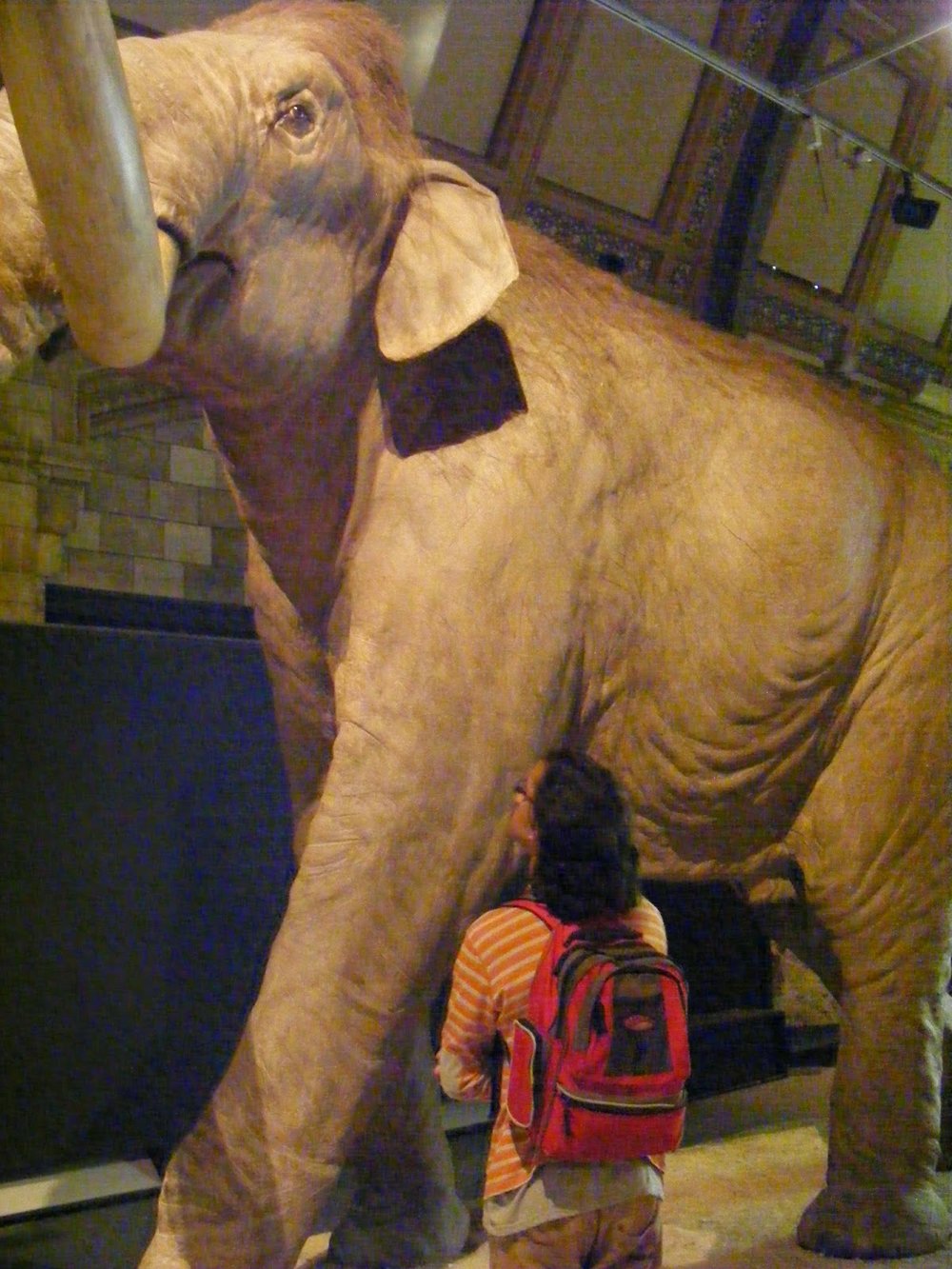

This guy is Huge!

Size comparison, thanks to Liam

Skull of a dire wolf

By slicing tusks in half and looking at them under UV light, scientists can tell how old the mammoth was when it died, what time of year it was and how healthy there were.

The pygmy mammoth, about the size of a large horse, was a separate species from the woolly and Colombian mammoths; it was specially adapted to island life. On islands, smaller mammoths had the advantage, as they ate less and were agile enough to navigate the hilly terrain.

Lost count of the number of times we’ve been to the museum, and still I discover things I’d not noticed before … We were sat on a bench outside, having our lunch, looking up at the building, when Liam pointed out the birds on the ‘railing’ right at the top …

This is the first time we’ve had a closer look at this sculpture … the detail is amazing – there’s a butterfly on the tail of the big cat that’s caught the attention of the cat on the left, which has a lizard on its tail …

Had a quiet sit-down while the boys went to bond with the T-rex in the dinosaur section … walked under this arched section enough times over the years on the way to the toilets, but only now noticed the birds on it …

There’s a section on the first floor called ‘Treasures’ – an eclectic mix of the museum’s favourite and valuable pieces, including the Archaeopteryx; “the earliest known bird … the Natural History Museum cares for the first skeleton specimen ever found. This spectacular fossil helped prove that modern birds evolved from dinosaurs and was the first example providing support for Darwin's theory of evolution. It is the most valuable fossil in the Museum's collection.”

And this beautiful shell of the nautilus, Nautilu pompilius, originally owned by Sir Hans Sloane, probably the most important collector ever; his huge collection, which he gave to the nation, forms the core of what is in the Natural History and the British Museums. This shell was carved by Dutch artist Johannes Belkien in the late 1600s.

Before heading off home, we met my sister, her hubby and her girlies for an early dinner – lovely end to the day.