Robert Falcon Scott's Last Expedition

Went up to London on Tuesday with the boys and our lovely friend, Hatty, and 2 of her kids. It has been many moons since she’s been to the museum; she’s a touch nervous about travelling around London on her own, even more so with kiddies in tow.

Decided to go before the school’s break up for the summer holidays, and I’ve been wanting to visit the Scott exhibition … downside with Gordon being at college, we haven’t got many ‘free’ days to play with. Anyway, as it turned out, for the first time ever, we had to queue to get in!! For about 20 minutes!!! Why? Because of the seemingly infinite number of school groups visiting the museum … they get priority.

The exhibition marks the centenary of Scott reaching the South Pole, and his last expedition in 1910-1913, the Terra Nova. It was fascinating and tremendously moving; as we got to the end, Hatty and I were fighting back tears. Weren’t allowed to take photos, which was a shame as there were the actual artefacts used by Scott’s team and a smidgen of the thousands of scientific specimens they found. There was footage in various videos dotted around the exhibition, and also a life-sized representation of Scott’s hut that survives in Antarctica, on Ross Island.

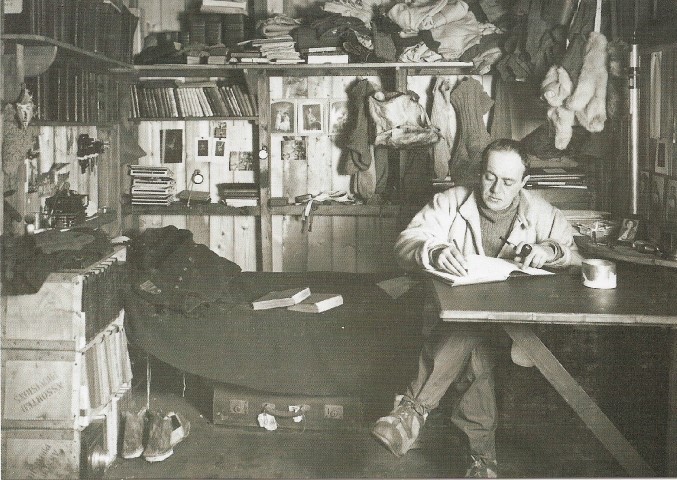

Scott's cubicle in the hut

Bunk beds for the officers

Scott's 43rd birthday, 6 June 1911

It shows how the men lived; Scott had his own cubicle, the officers slept in the middle of the hut, the kitchen was at the back of the hut where the seamen slept. The central table was their place of work, study, and the main eating area. They had to take all their provisions with them, which included familiar names like Rowntree’s, Fry’s Cocoa, Tate & Lyle … There were also displays of their letters and diaries.

The exhibition certainly opened my eyes to the fact that a lot of the expedition was to do with scientific explorations. The worst must have been the hellish journey to Cape Crozier, chronicled by Apsley Cherry-Garrard in his book, ‘The Worst Journey in the World’. Cherry-Garrard and Henry Bowers accompanied zoologist Edward Wilson on a 200km round trip from Cape Evans (their base) to Cape Crozier to collect emperor penguin eggs during the birds’ winter breeding season. The hypothesis at the time was that the embryos in the eggs might shed light on how birds evolved, and the evolutionary link between reptiles and birds.

The conditions were unimaginably hard; it was dark all the time, they didn’t know what time of day it was … they were getting frostbite even within their sleeping bags at night.

After 3 weeks, they finally reached the penguin rookery and, despite the dark and being unable to see what they were doing, they managed to slip down holes in the cliffs and get 5 eggs. Unfortunately, Cherry-Garrard slipped and broke 2 eggs. They carefully put the remaining 3 eggs into their fur mitts.

The journey back wasn’t any easier; Bowers fell through a crevasse and, luckily, was saved by the leather straps that attached him to the sledge. They were without food for 2 days and 2 nights, sucking melted ice from their sleeping bags to stay alive. They finally returned to Cape Evans 5 weeks after they'd set off.

Sadly, by the time the results of the embryo studies were published about 20 years later, the idea of penguins as an evolutionary link had been dismissed. The embryos for which so much had been risked, in the end, contributed little of scientific importance.

Leaving the hut area of the exhibition, the story continues with the journey to the South Pole. Each time the men went out on a scientific venture, they had to pile on layers of clothing and special footwear to protect against the cold. On the final hazardous journey, Scott and his team would remove only their outer layer and boots for sleeping. These would freeze solid overnight and it could take more than an hour to force them on again in the morning.

On 17 January 1912, Scott and his four companions – Capt. Lawrence Oates, Petty Officer Edgar Evans, Lt. Henry Bowers and Edward Wilson – arrived at the South Pole. Unfortunately, they had been beaten by Roald Amundsen’s team, who had arrived on 14 th December 1911. “The Norwegians have forestalled us and are first at the Pole. It is a terrible disappointment,” wrote Scott in his diary.

On their return journey, Evans died in mid-February. Scott’s journal entry on either March 16th or 17th: “Should this be found I want these facts recorded. Oates’ last thoughts were of his Mother, but immediately before he took pride in thinking that his regiment[6 th Iniskilling Dragoons] would be pleased with the bold way in which he met his death … He has borne intense suffering for weeks without complaint … He did not – would not – give up hope to the very end. He was a brave soul … He slept through the night before last, hoping not to wake; but he woke in the morning – yesterday. It was blowing a blizzard. He said, ‘I am just going outside and may be some time.’ He went out into the blizzard and we have not seen him since.”

Scott, Bowers and Wilson sheltered from the unrelenting blizzards, their food provisions gone. Scott’s final journal entry on the 29th March: “Every day we have been ready to start for our depot 11 miles away, but outside the door of the tent it remains a scene of whirling drift. I do not think we can hope for any better things now. We shall stick it out to the end, but we are getting weaker, of course, and the end cannot be far. It seems a pity, but I do not think I can write more. R.SCOTT. For God’s sake look after our people.”

I cannot begin to imagine what it must be like, stuck in that situation, knowing the supply depot is only 11 miles away…

On 12 November 1912, a search party found the tent and the bodies of Scott, Wilson and Bowers, including Scott’s diary. The bodies were buried under the tent, with a cairn of ice and snow to mark the spot, and a cross was fashioned from skis. A sledge was thrust into a smaller cairn nearby. It was a number of months before the news reached New Zealand and the rest of the world.

I’m so glad we made the effort to go to this exhibition; we learned a lot, and I can’t believe I was so ignorant of so much of it. Found this excellent site, which chronicles the expedition.

After lunch, we went to the Mammals section, then the Dinosaurs. I’m pretty sure we’ve never seen the twin narwhal tusks before …

If all the exhibits were removed from the museum, there would still be so much to see - the building, the walls, the pillars, the ceilings ... These are a couple of the pillars in the Dinosaur section ...

Lost count of the number of times we've been to the Natural History Museum over the years, and we're still not bored with it!